Everywhere about us was the sense of the pioneer, and of courage, which is never remote in Israel.

—J. Robert Oppenheimer, December 1958

On April 26, 1967, the Board of Governors of the Weizmann Institute of Science convened in Rehovot, Israel. The new president of the Institute, Meyer Weisgal, lieutenant of the late Chaim Weizmann, had a scoop for the press. “Had fate not intervened,” reported the newspaper Ma’ariv, “the president standing before the Board might have been the ‘father of the atomic bomb,’ Dr. Robert Oppenheimer.”

Weisgal revealed that six months prior to Oppenheimer’s death, he had conducted “secret” talks with the famed physicist, offering him the presidency of the Weizmann Institute. (At the time, Weisgal was trying to fill the vacancy at the top with someone other than himself.) In Weisgal’s telling, Oppenheimer accepted the offer, provided the Institute met certain conditions. “Conditions accepted,” Weisgal had replied. But “fate,” in the form of throat cancer, had stolen Oppenheimer away. He died on February 18, before anyone learned of the plan.

Weisgal repeated his account in a bit more detail in his memoirs, published in 1971:

I asked Oppenheimer if he would consider accepting the presidency of the Institute. We talked about it, alone, and then with his wife, Kitty. Shirley [Weisgal’s wife] and I visited them a number of times and continued the conversation. Finally he said: “I will accept the job on the following conditions. One, I must come back to the United States three months every year because I don’t want to give the impression of running away after what has happened; two, I will not do any entertaining. You will have to do it for me but I will be present whenever you call me; three, I will want to continue to do some physics.” I accepted all three conditions and we made a date to meet a few months later when I would again be in New York. When I returned and called his secretary I was given the shocking news that he was dying of cancer. No one could see him. A few months later he died. His funeral was one of the saddest experiences in my life.

(After Oppenheimer died, and one or two other candidates fell through, Weisgal reluctantly assumed the presidency of the Institute.)

It’s a remarkable story. But is it true? It’s not mentioned in any study of Oppenheimer. You won’t find it in Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Oppenheimer, American Prometheus (on which the 2023 Oscar-winning movie is based), or in Mark Wolverton’s A Life in Twilight: The Final Years of J. Robert Oppenheimer. I’ve found no other evidence for it, either in Oppenheimer’s private papers or in the archives of the Weizmann Institute. At this point, the sole source for the story is Weisgal.

In the absence of corroboration, Weisgal’s account can’t be verified. But is there any sense in which that account might be plausible? Does any evidence suggest that Oppenheimer might have thought to write one last chapter in his life, as president of the Weizmann Institute in Israel?

The pursuit begins

Any answer must begin with Meyer Weisgal, an irrepressible impresario and charming schmoozer whose contributions to Zionism and Israel haven’t received their due. Elie Wiesel found him to be “high in color, picturesque, even flamboyant,” a “trouble-shooter” and “amateur in all things” who “brings to mind a character of the Renaissance.” Isaiah Berlin called him “a man of farouche independence of character, whom nothing can bend or divert from the fixed purposes of his life, his Zionism.”

In these years, Weisgal pursued one paramount goal: winning international recognition for the young Weizmann Institute as a powerhouse of science. After Chaim Weizmann’s death in 1952, Weisgal took over the management on an “acting” basis. He was not a scientist, but he could map scientific excellence and sell it to Jewish donors who knew no physics, chemistry, or mathematics. Experience had also taught him to identify a Jew in distress. That description fit Oppenheimer perfectly in the early 1950s, when the architect of the Manhattan Project, now director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, lost his security clearance in the midst of the Red Scare.

Weisgal sought to draw Oppenheimer to the Weizmann Institute as early as June 1954, on a visit to Princeton. “The very day I was to meet him,” he recalled, “the New York Times carried a seven column news story: ‘Oppenheimer Declared Security Risk.’” At that first meeting, Weisgal invited Oppenheimer to visit Israel in the fall. Oppenheimer demurred; he doubted he’d be allowed to leave the country. But Weisgal didn’t give up: “If you find it impossible to arrange to come to Israel this year, the invitation is hereby extended without statute of limitation. Any time or any season, no matter for how long or how short a stay, you will, I assure you, be a most honored and welcome guest in Israel and the Weizmann Institute.”

Weisgal kept inviting Oppenheimer every year, and his persistence finally paid off. In May 1958, Oppenheimer made his first trip to Israel, to help inaugurate a new building for nuclear science in Rehovot. (I recently published his Rehovot speech for the first time, here.) In November, the Weizmann Institute Board of Governors elected Oppenheimer a member, and in December he delivered another speech at an Institute fundraiser in New York City. (I republished part of that speech as well, here.) Oppenheimer returned to Israel a second time in 1965, for a meeting of the Board of Governors. During the intervening years, Weisgal continued to cultivate Oppenheimer. They addressed one another in increasingly familiar terms in their letters, and Weisgal befriended Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty.

So it’s not hard to document Oppenheimer’s growing ties to the Weizmann Institute from 1954 to 1965. It’s amply attested in the press and in his own papers.

A Jewish spark?

There is also some anecdotal evidence that Israel stirred a sense of solidarity in Oppenheimer. Weisgal described him as “strangely alien to Jewish life and all its implications, but Rehovot and Israel fascinated him…. During one of our conversations, he spoke to me about his impressions of Israel. I don’t remember his words but I remember clearly that his voice was choked and there were tears running down his face.” Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, who met with Oppenheimer during his 1958 visit, told the Israeli cabinet that “when I briefly met Oppenheimer in Rehovot, I had the impression, though I can’t be sure, that some sort of Jewish spark lit up the man.”

It might be argued that Weisgal and Ben-Gurion were primed to detect even the faintest hint of sympathy. One finds firmer evidence in the actual words spoken by Oppenheimer in an interview he gave to a Ma’ariv writer (and future politician) Geulah Cohen, during his 1965 visit. (Although it was published in Hebrew, the Weizmann Institute archives preserve a copy of the text in the English, which I’ll presume to be his words and not a translation. I’ll quote it directly.)

“I should like to confess,” Oppenheimer told his interviewer, “I am not a believer. Not that I am an atheist or that I claim that there is no God. I am an agnostic, I do not know.” Question: did he believe the return of the Jews to Zion and sovereignty “are prerequisites for the fulfillment of the Jewish destiny?” “I’m not sure about that from a cultural point of view,” Oppenheimer answered.

After all, Judaism was preserved, and thrived even in Exile, but—who knows, it may be possible for Judaism to contribute even more within this sovereign framework. Please understand me. I greatly esteem the deep feelings you have here, and I even envy them. But I don’t share them myself. Anyway, I’m here, and not just because I like long air-flights. What I meant to say before was only that I do not think that the Law which will save the world must necessarily come from Zion.

So the reader was left hanging: Oppenheimer was not a Jew by belief or a Zionist by ideology, yet here he was.

Hope and nostalgia

Perhaps there is a further hint in the two public speeches Oppenheimer delivered for the Weizmann Institute in 1958. On both occasions, he spoke of Israel as a preserve of a certain spirit that had gone missing in the West. “As an outsider coming from America,” he said in his Rehovot speech,

I can say that the whole world sees in Israel a symbol, and not just a symbol of courage, and not just a symbol of dedication, but of faith and confidence in man’s reason, and a confidence in man’s future, and in the confidence in man, and of hope. These are all now largely and sadly missing in those vast parts of the world which not so long ago were their very cradle.

Israeli society, he told his New York audience a few months later, was “forced by danger, by hardship, by hostile neighbors, to an intense, continued common effort.” As a result, “one finds a health of spirit, a human health, now grown rare in the great lands of Europe and America, which will serve not only to bring dedicated men and dedication to Israel, but to lead us to refresh and renew the ancient sources of our own strength and health.”

This notion that Israel preserved a sense of purpose that had been lost in the West also arose in Oppenheimer’s conversation with Ben-Gurion, as reported by Ben-Gurion nine years later, just after Oppenheimer had died. Ben-Gurion was interviewed on the NBC television program Meet the Press. The interviewer asked: “Can you tell us why any American Jew should leave this rich, prosperous country to come to the Negev?”

Ben-Gurion said he’d already put just that question to Oppenheimer: would American Jewish scientists come to Israel? “McCarthy is gone,” Ben-Gurion had told him, “and a Jew is not being discriminated now. Will they come?”

[Oppenheimer] said yes. I said, why? He said, I will tell you. There are two types of human beings. One, this is the majority, who wants to take, to get. There is another type, yet a minority, who has a great deal to give, to create. And this is the meaning of life. There is no meaning of life in America, in England and France, that’s what he said. I asked is there meaning of life here in Israel? He said before I came I was told there is and when I came I saw there is.

The intimacy of science in the small state of Israel also seemed to appeal to Oppenheimer. He explained this in his New York speech:

Part of the nostalgia which touches the foreign visitor to Israel lies in the sense that in Israel still, despite its great growth, there is a human community of manageable size. Men can talk together as friends, and need not deal with one another through committees, delegations, memoranda, and the inevitable proliferation of pigeon holes and clerks.

By contrast, “we in the super powers, in one way or another, are entangled in this problem of size.” Israel, he imagined, would eventually face the same problem as its needs grew. But “as of today Israel still has a reprieve from the curse of bigness, and serves to remind us what a small band of devoted men can do when they can understand one another as friends, and can build a common purpose on a common experience and shared knowledge.”

The resort to the word “nostalgia” is telling here, although it isn’t clear whether Oppenheimer was harking back to a lost Arcadia before the world war, or the “devoted” (but still very large) community he built during the war at Los Alamos. In any event, this ideal of “quiet intimacy” stood in clear contrast to the “big science” of the post-war, and Israel seemed to embody it.

Israel also lavished attention on Oppenheimer, and this may have had an effect. On that 1958 visit, not only did he meet publicly and privately with Ben-Gurion. He was received by Israel’s president, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, and met the foreign minister, Moshe Sharett. In 1965, he was received by Levi Eshkol, Ben-Gurion’s successor as prime minister. On that visit, Oppenheimer was flown to Eilat by military plane, accompanied by Ernst David Bergmann, the head of Israel’s Atomic Energy Commission, along with Shimon Peres, then director-general of the defense ministry. (“Yesterday, I flew over the Dead Sea,” he told Geulah Cohen. “I saw Sodom and I thought how easy it was to live then, in a world where all the evil was limited to one place.”)

And it wasn’t just the political elite that embraced him. An observer in 1958 wrote that Oppenheimer had “captured the heart and mind of Israel…. Wherever he appeared he was surrounded by autograph hunters. His lectures on purely scientific subjects were crowded to capacity. Men and women, young and old, literally fought for admission.”

That Oppenheimer warmed to Israel over time seems indisputable, although the reasons appear idiosyncratic. They seem wholly unrelated to Judaism or Zionism; nor did Oppenheimer ever adduce the Holocaust.

That it happened at all was due primarily to the mediation of Meyer Weisgal, “To know him,” said Oppenheimer, “and above all in his beloved Rehovot, is one of the very good things of this world.” This was no small irony. Elie Wiesel once wrote of Oppenheimer that “he remained at a distance from Yiddishkeit.” But in allowing Weisgal to befriend him, he closed some of the gap. Weisgal hailed from the other side of the Jewish world. “Like most Jews,” Weisgal wrote in his memoirs, “I was born in Kikl,” a typical Polish shtetl, and he perfectly preserved its qualities. One interviewer called him “one of the few genuine shtetl Jews still extant.”

Weisgal’s genius was that he could lay a bridge between shtetl and science for others to cross. Thus, for example, did Oppenheimer find himself addressing that Weizmann Institute fundraiser in New York, where “the applause was most voluptuous when artists sang chasidic tunes in Yiddish.”

A departure and a vacancy

That brings us back to Weisgal’s specific claim that he’d successfully recruited Oppenheimer to join him in Rehovot, to preside over the Weizmann Institute. It was one thing for Oppenheimer to be of occasional service to the Institute or broadly sympathetic to Israel. But the commitment alleged by Weisgal went far beyond both.

It obviously depended on some seating changes. First, Oppenheimer had to become a free agent. That happened in the spring of 1965, when he decided he would end his reign as director of the Institute for Advanced Study after 19 years. His term would conclude in June 1966. When Oppenheimer attended the Weizmann Institute’s Board of Governors meeting in October 1965, everyone in the room knew he’d called it quits. (It had been reported in the Israeli press too.)

In 1958, Oppenheimer had come as a guest. In 1965, he had responsibilities. Weisgal convened the meeting in crisis mode, prompted by a cash crunch that would require “a radical reorganization and financial retrenchment.” The government might step in, but only if the research agenda focused more on its needs. Oppenheimer conveyed the urgency to the press: “I came because Mr. Weisgal phoned me and told me that this was going to be a very important meeting.” According to another press report, Oppenheimer plunged into the deliberations, making ten interventions and dissecting the planned budget.

His interview in Ma’ariv, his first to an Israeli newspaper, raised his profile still further. General interest in him also ran high: his visit corresponded with a Tel Aviv production of Heinar Kipphardt’s play about him (one he detested). His name was in the newspapers every day.

And there was that flight to Eilat. Oppenheimer didn’t need Bergmann and Peres to show him around the scruffy desert town. This was quality time on a military aircraft, spent with the two leading architects of Israel’s nuclear program, while flying close to Israel’s secret equivalent of Los Alamos: Dimona. Perhaps in future, a classified document will reveal more about this day trip. But public word of it was clearly meant to show official interest in Oppenheimer.

Still, setting Weisgal in motion required a second seat change. That occurred when Abba Eban, who had served as the titular president of the Weizmann Institute since 1959, announced his impending departure. (He would become Israel’s foreign minister in January 1966.) The vacancy at the top sent Weisgal into full search mode; this time he resolved to find a scientist for the position.

According to his memoirs, he didn’t start with Oppenheimer. He first tried to recruit Victor Rothschild, 3rd Baron Rothschild, whose name nearly said it all, except that he was a zoologist and therefore a scientist too. But Victor kept eluding him (indeed, his authorized biography is entitled The Elusive Rothschild) and so Weisgal moved on to Oppenheimer. This time he succeeded.

“The shocking news…”

Or did he? Weisgal, when he first revealed the story, placed the negotiation six months before Oppenheimer died—that is, during the summer of 1966. This is where the trouble begins.

The previous February, Oppenheimer had been diagnosed with throat cancer. In March he underwent an operation and cobalt radiation therapy. (Word of his illness reached Chaim Pekeris, a mathematician and physicist at the Weizmann Institute and a personal friend. Pekeris wrote to him in April about the “sad news,” wishing him a speedy and full recovery.) In July Oppenheimer seemed better, and he informed the Weizmann Institute that he would attend the next board meeting in Israel, scheduled for the end of April 1967. Kitty would accompany him. He died well before that.

So is it plausible that in 1966, Oppenheimer, grappling with an aggressive cancer while growing visibly weaker, said yes to the Weizmann Institute and life in Israel? Not only is there no corroboration for Weisgal’s account. In Weisgal’s own (apparent) last letter to Oppenheimer, written on July 25, there is no hint of any pending or urgent business:

I shall not be back in the States until sometime in October. May I get in touch with you then? I was very happy to see among my correspondence that you are coming to our meeting next spring. That will be wonderful.

Neither is there the expression of concern over Oppenheimer’s health that one would expect from a close associate. Weisgal, back from fundraising abroad, breezily complained about the need “to extract money from unwilling pockets,” told him that the Weizmann Institute had installed a swimming pool, and ended with his “warmest personal regards” in a matter-of-fact way. Weisgal seems not to have known of Oppenheimer’s condition. (He basically admitted as much in his memoirs: “When I returned and called his secretary I was given the shocking news that he was dying of cancer…. A few months later he died.”)

If it didn’t happen the way Weisgal said it did, might he have imagined or fabricated the whole thing? Here, too, there is a problem. According to him, one other person was privy to the “secret” negotiation: Kitty Oppenheimer. “We talked about it, alone, and then with his wife, Kitty.” When Weisgal first told his story in 1967, and published it in his memoirs in late 1971, she was still alive. (She died of an embolism in October 1972.) Would he have risked being contradicted by Oppenheimer’s widow? That, too, seems improbable.

In sum, Weisgal has left us a mystery. There are intermediate scenarios that might fill in the gaps, but they are all speculative. One might as well quote Oppenheimer, from his Ma’ariv interview: “I don’t believe it is ever possible to describe complete truth: man always compromises.” Or Weisgal from his memoirs: “Everybody has his own version of history, of the truth, of what really happened.”

In mid-October 1966, Meyer Weisgal was elected president of the Weizmann Institute. (“It was, at best, another stop-gap measure,” he wrote.) If there ever was an Oppenheimer option, it had vanished.

Need for revision

Oppenheimer “had his ‘Bar Mitzva’ very late, actually through his association with the Weizmann Institute.”

So wrote Amos de-Shalit, a nuclear physicist and Weisgal’s number-two, to the Institute’s representative in Europe in April 1967. “As you may know, four months before his death he actually agreed to take on the position of a President of the W.I.” De-Shalit and Weisgal thought to memorialize Oppenheimer by naming a lab after him. That would require a donation of a million dollars. “It must be done fast,” wrote de-Shalit.

I am sure we are not the only laboratory which intends to set up a memorial for Oppenheimer, and being outside the US, we cannot be second or third. To people who did not know of Oppenheimer’s return to Judaism it would smell too much of ‘me too.’

In fact, no one would have known of Oppenheimer’s “return to Judaism,” because it never happened in the way that phrase is commonly used. But if bar mitzvah is understood in the sense of assuming responsibilities as a member of the Jewish people, it’s not an unreasonable description of what Oppenheimer underwent “very late” in his life. If so, then the usual portrait of Oppenheimer as utterly alienated from his Jewish origins needs some revision, at least for his last years.

There has been much discussion of Oppenheimer’s fascination with the Bhagavad Gita, which he’d studied with a Berkeley Sanskritist. There are virtually no references to his knowledge of the Hebrew Bible. There is a passage in the Ma’ariv interview that fills that empty space, in a modest and belated way.

Only a few days ago in California, I awoke unusually early in the morning, on a day I was due to lecture at the University. I was shivering with fear. I picked up a Bible and began to read Ecclesiastes. Suddenly I felt the blood returning to my veins, warming my heart. I had discovered Ecclesiastes. It is a tremendous book. A marvelous book! It contains a combination of the two elements essential to life in our world—the idea of Man’s duty, that all is determined, that Man has no choice, that he must fit himself into the closed circle of regulation. And, also, it has a lofty humor: From your little place in the world, you look out, in sadness tempered with a smile, perhaps even a chuckle. It is a chuckle which seems to say: ‘You will have to fit into the circle anyway, so better smile and go round with it willingly, but do not for a minute think that it is you who powers the circle.’

Oppenheimer had “discovered Ecclesiastes” at the age of 61, in tandem with his discovery of Israel. What else might he have discovered, if given more time, of the people, the tradition, and the land of his forebears? One can only imagine.

Main sources: Meyer Weisgal, Meyer Weisgal… So Far; An Autobiography (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971), 359-60 [the claim about Oppenheimer]; Ma’ariv, April 26, 1967 [first version of the same claim]; Ma’ariv, October 29, 1965 [Geulah Cohen’s interview with Oppenheimer]; Weizmann Institute Archives, file 14-75(5) [English version of Cohen interview, typescript]; Lawrence E. Spivak, prod., Meet the Press, March 5, 1967 (New York, NY: NBCUniversal, 1967), video file (29 min.) [Ben-Gurion recalls Oppenheimer on Jewish scientists]; J. Robert Oppenheimer, Science and Statecraft (New York: American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science, 1958) [Oppenheimer’s 1958 speech to New York fundraiser for Weizmann Institute]; J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, box 287, folder 7 [Oppenheimer’s 1958 speech in Rehovot; also here]. Acknowledgement: Special thanks to the Weizmann Institute Archives (Mati Beinenson).

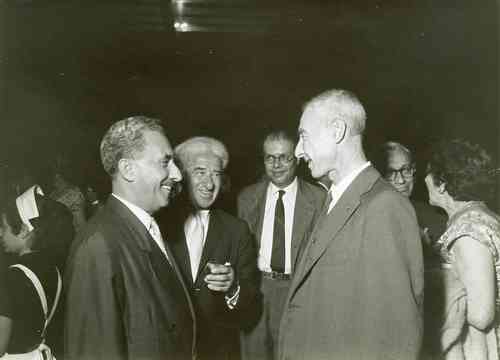

Image header: J. Robert Oppenheimer (right) and Meyer Weisgal at the Weizmann Institute, May 20, 1958; photograph by Boris Carmi, Meitar Collection, The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection, The National Library of Israel.

You must be logged in to post a comment.