In May 1958, J. Robert Oppenheimer travelled to Israel to celebrate a new institute for nuclear science at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot.

This event became a landmark in the relationship between Oppenheimer and the Weizmann Institute, between the “father of the atomic bomb” and Israel. It’s been little noted, because Oppenheimer is generally considered to have been distant from his Jewish origins and disconnected from Zionism and Israel.

Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, in their Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Oppenheimer, American Prometheus (on which the 2023 movie is based), make much of the testimony of Isidor Isaac Rabi, a dedicated Jew, physicist and 1944 Nobel laureate who had been an adviser to the Manhattan Project. “Oppenheimer was Jewish, but he wished he weren’t and tried to pretend he wasn’t.” And this: “I don’t know that he thought of himself as being Jewish. I think he had fantasies thinking he was not Jewish.” Bird and Sherwin conclude that Oppenheimer had “a lifelong ambivalence about his Jewish identity.” As for Israel, they make no mention of the Weizmann Institute, and refer to the 1958 visit as one stop tacked on to a European tour. The Weizmann event is mentioned in a passing manner in Mark Wolverton’s A Life in Twilight: The Final Years of J. Robert Oppenheimer, again as an add-on to Europe.

However ambivalent Oppenheimer may have been about his Jewish identity, his relationship with the Weizmann Institute and Israel gained momentum in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when he would travel to Israel again. Indeed, there’s even an overlooked mystery to be resolved, but I’ll save it for a later post. In this post, I’ll bring the words spoken by Oppenheimer at the Weizmann Institute on May 20, 1958.

The text may help to explain a remark made by Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion to the Israeli cabinet, after he’d met with Oppenheimer at the latter’s request. Ben-Gurion said he “had the impression that some sort of Jewish spark lit up the man.”

That impression may have originated in Oppenheimer’s speech. Ben-Gurion certainly heard it. The prime minister delivered the keynote at the same dedication, and sat with Oppenheimer in the front row. Oppenheimer, in his own speech, made several references to Ben-Gurion’s remarks. (When Oppenheimer said “It is not only the Prime Minister of Israel who has his difficulties,” he was referring to Ben-Gurion’s admission that he didn’t understand much about physics.)

What’s the source for Oppenheimer’s text? Oppenheimer spoke from notes, but he didn’t have a copy of the speech as he delivered it. “I gave my notes on the ceremonial talk to your press officer,” he wrote to Meyer Weisgal, his host, “and have no record at all of what I said.” At Oppenheimer’s request, the Weizmann Institute sent him a tape with the extract of his speech, secured from the Voice of Israel, which had broadcast the proceedings. The following text is a transcription of the delivered speech, from Oppenheimer’s papers. While the Jerusalem Post reported a few portions of his remarks the day after he spoke, the speech is published here in full for the first time.

I’ve appended an extract from another speech that Oppenheimer gave for the Weizmann Institute on December 2, 1958, at its annual fundraiser at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. There Oppenheimer reflected on his visit to Israel the previous May. It complements the Rehovot speech.

Some of the persons mentioned by Oppenheimer in the two speeches:

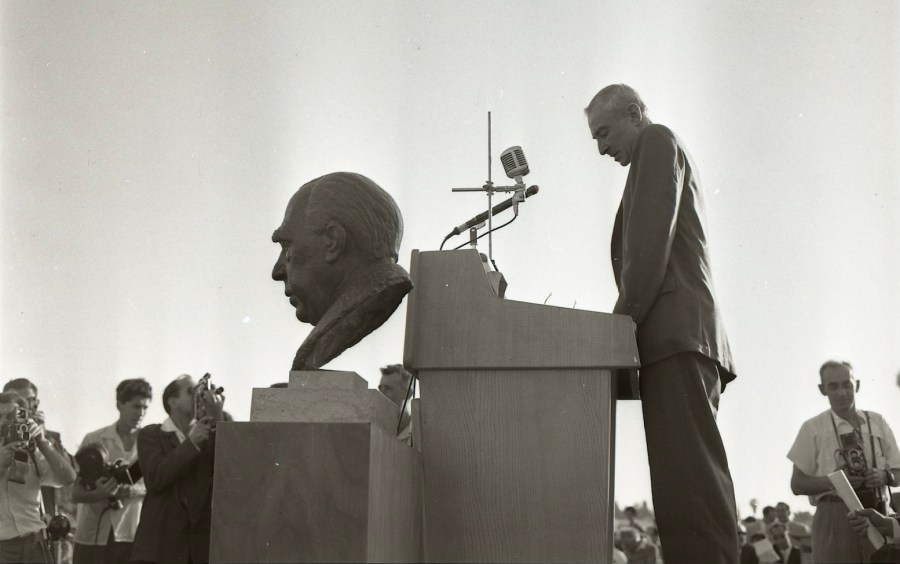

- Niels Bohr, Danish physicist and 1922 Nobel laureate. Although baptized a Lutheran, his mother came from a distinguished Jewish family, so he fled Denmark during the Nazi occupation. He later assisted Oppenheimer in the Manhattan Project. Bohr had already lent his prestige to the Weizmann Institute during an earlier visit in 1953, and he also spoke at the 1958 dedication, for which the Institute commissioned his bust.

- Meyer Weisgal, Zionist author and fundraiser, and confidant of the late Chaim Weizmann. At this time, he was chairman of the executive council of the Weizmann Institute. He would become the person in Israel closest to Oppenheimer.

- Benjamin Bloch, physicist by training, administrator of the Weizmann Institute, and a friend of Bohr and Oppenheimer. (Felix Bloch, the Swiss-American physicist and 1952 Nobel laureate, also attended the 1958 dedication, but Oppenheimer’s reference to “Dr. Bloch” clearly refers to Benjamin.)

- Abba Eban, Israeli statesman. In late 1958, he was at the end of his service as Israeli ambassador to the United States and chief delegate to the United Nations, and had been named the next president of the Weizmann Institute.

- Ernest (later Lord) Rutherford, New Zealand-British physicist and 1908 Nobel laureate, a friend to Chaim Weizmann in Manchester.

Header image: J. Robert Oppenheimer speaks at the Weizmann Institute before a bust of Niels Bohr, May 20, 1958; photograph by Boris Carmi, Meitar Collection, The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection, The National Library of Israel.

Oppenheimer’s Rehovot speech, May 20, 1958

Mr. President, Mr. Prime Minister, Professor Bohr, Mrs. Weizmann, Mr. Weisgal, my colleagues, Ladies and Gentlemen. It is a multiple pleasure, as it is a deep honor, to participate in this celebration. We are celebrating many things. I will speak of three. This is physics; this is Israel; this is for Bohr.

This wholly living and beautiful monument is a monument to the physics that has occurred here in the past, to the brilliant work well done. It is to be a future center, famous for all of us as is Bohr’s Institute in Copenhagen, not only for those who live here, but as a center for scholars and students from the whole wide world. It is a source of celebration and honor for the physicists here in this Institute in this country, for Mr. Weisgal and Dr. Bloch, and for the many who have given generously to make this center, and this building. And even here in Rehovoth, even in the amazing development of the Weizmann Institute which is so young, and has come against many obstacles so wonderfully far, this new center is, to anyone who comes for the first time, a most impressive and almost unbelievable structure and hope.

Physics is of course only a small part of learning; and we all know that even in an Institute like this not all physics can be done; though we also know that the scientists here will be friendly and hospitable to all progress in all fields everywhere. But we may be provincial for a minute. Physics, although it is only one of the sciences, has some lessons to teach; it has a very special part; it sets a very special example. It exemplifies—above all this physics of the microcosm—two traits of human experience; great novelty and adventure, great harmony and order. One cannot live in it without recognizing how limited even the greatest human experience of the past has been, without having a sense of the openness of the future. One cannot live in it without recognizing how limited and rather poor is the human imagination, without the guide of nature. And still it is a world of highest harmony and order, words which the Prime Minister used, although he is not a scientist, as a physicist would like to see them used—words which stood for Einstein for a kind of wonder and awe at the fact that this is not a world of chaos, that it is a world of beauty, that, in the marvelous phrase of Thomas Jefferson, nature is “fit for man’s comprehension.”

It is in no way an accident, or trivial, and for me perhaps it is the second most exciting part of the celebration, that it is here in Israel. I cannot speak to you who have fought, who have worked for more than ten years, to bring this country into being, who are destined to continue to do it, of what that means; I cannot be maudlin about it. But as an outsider coming from America, I can say that the whole world sees in Israel a symbol, and not just a symbol of courage, and not just a symbol of dedication, but of faith and confidence in man’s reason, and a confidence in man’s future, and in the confidence in man, and of hope. These are all now largely and sadly missing in those vast parts of the world which not so long ago were their very cradle.

And then this is for Bohr, who is not only a friend, a revered and honored friend of many of us but in many ways he laid the corner stone of this building, this Institute, and this hope. Five years ago he laid the actual physical corner stone of the building. He has laid as well the corner stone for that edifice of understanding to whose cultivation this building is dedicated. For the past half a century, since the Manchester days, when he was with Rutherford and Weizmann, Bohr has been the inspiration and guide to those who hoped to learn new truth about nature, and also to those who hoped from this to learn afresh our understanding of man himself, of his understanding, of his power, of his limits, of the nature of his knowledge, and the nature of his destiny. This sculptured head, this image of Bohr is here; it will be in the great hall of the Institute; it will be in one place. But, believe me, Bohr’s image is in the heart of every physicist.

New knowledge lends to man new power. This is nothing to stress here. The life of Israel would not be possible without it. It would not be possible to fight the difficulties, the adversities of nature, and the adversities which have been added by men; and I need not labor it. But among these powers there are powers of destruction, far too deadly to be used if human society is to endure at all. Professor Bohr was among the very first to understand this, and to think deeply about it, and to act with the highest and most enduring responsibility. In this too, he is for us a revered leader. He has written a most modest account of his views and his actions in an open letter to the United Nations. He has never let these thoughts wander too far from the center of his attention. For we live in a world in which the nations will have to learn to unite, to open their frontiers and their barriers to each other, and to lose those powers of making war, which are today an intolerable menace, and for whose use even today, some states are wholly lacking in incentive.

In this connection I have a hope, a confident hope, of another great role for Israel. The vastness, the variety of our world is beyond our compass. Our knowledge of nature and man doubles every decade, for the most part far beyond the reach of any total common understanding. It is not only the Prime Minister of Israel who has his difficulties. It is all of us. In all ways the pace of change is not attuned to the familiar pattern of man’s life. In this we have a heavy double duty: to be faithful to our own ways; to be open and friendly to the ways of others, as Israel has been, in welcoming to her land men of such varied cultures, tongues, customs and traditions. We must love and cherish what is our own, what we know: our own land, or the life of Israel; or our own work, the life of physics. Only so do we really live, do we live a life in depth and fullness. Yet we must lend a ready ear and give a welcoming hand to other cultures, and to other ways, strange ways, to art, to sciences, to learning, too vast, too rapidly growing and changing, for us to be quite at home with it. My hope and wish is that Israel may show to all the world, by its own great example, that there can be harmony between these two complementary needs and duties. This new Institute, guided by Bohr’s spirit, and the example of his own life, will be a source of pride and joy to Israel, and to physics, and yet be open to all other worlds, in fraternity, and in friendship.

Source: J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, box 287, folder 7.

Oppenheimer’s Waldorf-Astoria speech, December 2, 1958 (excerpt)

Just one month ago, Mr. Eban, the new President of the Weizmann Institute, the Ambassador of Israel to Washington, and the Chief Delegate of Israel to the United Nations, spoke for the Weizmann Day Assembly at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot. I was not there to celebrate and listen, but I have Mr. Eban’s thoughtful text. I am reminded of an earlier day, last May, when, as a member of a small group of visiting physical scientists, I also spoke in this same memorial square. We were there to celebrate the opening of the new Institute for Nuclear Sciences, the penultimate structure in the building program of the Institute, now happily complete.

It was a sunny and heartening occasion, bringing to all our minds the many themes which Weizmann’s name and his Institute have come to symbolize. Mrs. Weizmann was there, to make the past present; and the President and Prime Minister of Israel, attesting the place that the cultivation of science plays in the life of Israel. Niels Bohr was there; he had laid the corner stone of this building, attesting the interest of scholars and scientists throughout the world in this Institute, which has already seen so many beautiful contributions to our understanding of nature, and whose future seems to all of us so full of promise. Meyer Weisgal was there; to know him, and above all in his beloved Rehovot, is one of the very good things of this world.

We were in a garden, in land recently restored but already old in beauty. Everywhere about us was the sense of the pioneer, and of courage, which is never remote in Israel. Everywhere about us was the memory of Weizmann, with his double devotion to learning and to his people. Many of our colleagues of the Institute were well known to us, even those of us who had not before visited Rehovot: familiar figures at Geneva, Paris, Princeton, and wherever else that scholars are at work. For here at Rehovot we saw a happy blend that is characteristic of science and of Israel, and a hope for our time and the future: a warm love and pride in the Institute, in things local and close in geography and culture, and a wide-ranging, outgoing concern and appreciation for the whole international enterprise that is contemporary learning. Here we heard again the voice of a people long confident that virtue is possible on this earth, and has its place here, and that history is man’s high story, and our part in it marked by duty and touched with hope.

Indeed, for myself I learned not only of the land I was visiting, but of things relevant to the older, richer, larger societies of the Western world; for the Institute at Rehovot that day would have been intelligible and sympathetic to the men of the Enlightenment, or to the founding fathers of the United States—to Franklin perhaps most of all, or to Jefferson. In this society, forced by danger, by hardship, by hostile neighbors, to an intense, continued common effort, one finds a health of spirit, a human health, now grown rare in the great lands of Europe and America, which will serve not only to bring dedicated men and dedication to Israel, but to lead us to refresh and renew the ancient sources of our own strength and health.

Source: J. Robert Oppenheimer, Science and Statecraft (New York: American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science, 1958), pp. 3-4. The speech was republished five years later by Jacob Baal-Teshuva, ed., The Mission of Israel (New York: Robert Speller & Sons, 1963), pp. 94-95. Drafts of the speech are preserved in the J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, box 287, folder 6.

You must be logged in to post a comment.