Rashid Khalidi, the Edward Said Professor at Columbia University, is no fool. He started out as a

spokesperson for the PLO in Beirut in the 1970s, and he’s been at it ever since. A New Yorker by birth, he knows something about perceptions of the conflict in America. And he knows that terrorism has set back the Palestinian cause time and again. That’s why he’s spent much of his career trying to anesthetize America to terrorism, divert attention from it, or minimize it.

The horrific massacre of Israeli men, women, and children committed by Hamas on October 7 has made his mission much harder. “The current sentiment,” he

told an Arab interviewer (in Arabic),

politically, popularly, and in the media, is overwhelmingly negative. This contrasts sharply with the past decade, which saw growing support for Palestinian political rights and strong opposition to Israeli policies…. They’re capitalizing on the deaths of Israeli civilians during the Al-Aqsa Storm operation…. Having lived in the U.S., particularly New York, for over half my life, I’ve never seen such an onslaught of lies and crude propaganda that are actually making an impact.

Khalidi recommends a number of talking points to his followers. He’s dropped some in reaction to new and awful evidence, but one remains constant. Here is how Khalidi has

made it, on two separate occasions:

There are ways of making war, which advanced technological societies employ, which involve the killing of huge numbers of civilians, who are never somehow counted in the calculus. Oh, that’s collateral damage. Oh, we didn’t mean to do it. If a pilot does it from 1,000 feet, and kills fifty people, or some somebody with a gun comes in and murders fifty people, there is a difference, obviously, but in the last analysis, if this is a violation of the rules of war on the one hand, it’s a violation of the rules of war on the other hand… One kind of killing of civilians—only that kind—is called terrorism and another kind of systematic killing of civilians, with much higher death counts, is simply ignored.

And here,

another formulation of the same talking point:

Israeli lives should be considered civilian lives, should be considered important, obviously. Any civilian death should be mourned. But all people are supposedly equal…. The 900 or 1,000 Israeli civilians who died starting on the seventh of October, are now matched by a mountain of two or three times—it will soon be four times—as many Palestinians, again, like the Israelis, innocent civilians…. The rest of the world… do[es] not see the difference between Hamas or other militants coming out of Gaza killing civilians, and Israeli pilots, or Israeli gunners, or Israeli gunboats killing civilians. Killing civilians is killing civilians, especially in these numbers…. The world sees that, even as the American and European… media, which seem to move in lockstep with their governments, may distort this.

This talking point has become standard in many attempts to “contextualize” October 7. Queen Rania of Jordan made it in abbreviated form in a television

interview seen by millions: “Are we being told that it is wrong to kill a family, an entire family at gunpoint but it’s OK to shell them to death? I mean, there is a glaring double standard here. And it is just shocking to the Arab world.”

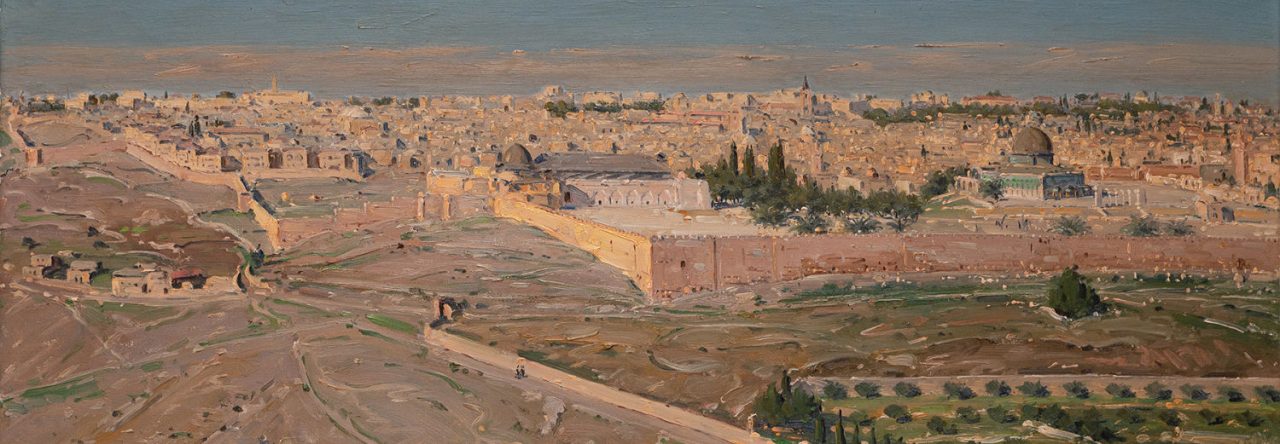

Embed from Getty Images

The ‘Dresden defense’

I am a historian (like Khalidi), interested in the origins of ideas and arguments. It turns out that Khalidi’s premier talking point has a very specific genesis.

It figured in the case for the defense in the

Einsatzgruppen Trial, conducted by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal from late 1947 to the spring of 1948. The

Einsatzgruppen were the paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany, which carried out mass murder by shooting in Nazi-occupied Europe. They destroyed well over a million Jews, and two million people all told. After the war, their surviving senior commanders were put on trial at Nuremberg, charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes.

The chief defendant, SS-Gruppenführer Otto Ohlendorf, had been commander of

Einsatzgruppe D, which carried out mass murders in Moldova, southern Ukraine, and the Caucasus. An economist and father of five, he had supervised the killing of 90,000 Jews. Ohlendorf imagined that he had a moral conscience. The killers under his command,

he told a U.S. Army prosecutor, were prohibited from using infants for target practice, or smashing their heads against trees.

Embed from Getty Images

During trial testimony, the prosecutor

pressed Ohlendorf: “You were going out to shoot down defenseless people. Now, didn’t the question of the morality of that enter your mind?” Ohlendorf referred to the Allied bombings of Germany as a context:

I am not in a position to isolate this occurrence from the occurrences of 1943, 1944, and 1945 where with my own hands I took children and women out of the burning asphalt myself, and with my own hands I took big blocks of stone from the stomachs of pregnant women; and with my own eyes I saw 60,000 people die within 24 hours.

A judge immediately pointed out that his own killing spree

preceded those bombings. But this would become known as the “Dresden defense,” to which Ohlendorf resorted still another time, in

this exchange:

Ohlendorf: I have seen very many children killed in this war through air attacks, for the security of other nations, and orders were carried out to bomb, no matter whether many children were killed or not.

Q: Now, I think we are getting somewhere, Mr. Ohlendorf. You saw German children killed by Allied bombers and that is what you are referring to?

Ohlendorf: Yes, I have seen it.

Q: Do you attempt to draw a moral comparison between the bomber who drops bombs hoping that it will not kill children and yourself who shot children deliberately? Is that a fair moral comparison ?

Ohlendorf: I cannot imagine that those planes which systematically covered a city that was a fortified city, square meter for square meter, with incendiaries and explosive bombs and again with phosphorus bombs, and this done from block to block, and then as I have seen it in Dresden likewise the squares where the civilian population had fled to—that these men could possibly hope not to kill any civilian population, and no children.

Ohlendorf thought this defense so powerful that he

invoked it yet another time:

The fact that individual men killed civilians face to face is looked upon as terrible and is pictured as specially gruesome because the order was clearly given to kill these people; but I cannot morally evaluate a deed any better, a deed which makes it possible, by pushing a button, to kill a much larger number of civilians, men, women, and children.

(The chief prosecutor, an American, called this particular iteration “exactly what a fanatical pseudo-intellectual SS-man might well believe.”)

At Nuremberg, this sort of

tu quoque defense (“I shouldn’t be punished because they did it too”) wasn’t admissible. Still, in the verdict of the

Einsatzgruppen Trial, the judges chose to refute it. “It was submitted,” the judges wrote, “that the defendants must be exonerated from the charge of killing civilian populations since every Allied nation brought about the death of noncombatants through the instrumentality of bombing.” The judges

would have none of it:

A city is bombed for tactical purposes… it inevitably happens that nonmilitary persons are killed. This is an incident, a grave incident to be sure, but an unavoidable corollary of battle action. The civilians are not individualized. The bomb falls, it is aimed at the railroad yards, houses along the tracks are hit and many of their occupants killed. But that is entirely different, both in fact and in law, from an armed force marching up to these same railroad tracks, entering those houses abutting thereon, dragging out the men, women and children and shooting them.

The tribunal sentenced Ohlendorf to death. He was hanged in June 1951.

“In the last analysis”

Nuremberg enforced a fundamental distinction. All civilian lives are equal, but not so all ways of taking them. The deliberate and purposeful killing of civilians is a crime; not so the taking of civilian lives that is undesired, unintended, but unavoidable. The errors made by a bomber squadron cannot be deducted from the murders committed by a death squad. It’s a difference compounded many times over when those civilian men, women, and children are subjected to torture, rape, and mutilation before their murder. To borrow Khalidi’s phrase, “in the last analysis,” this distinction is what separates modern civilization from its predecessors.

More disturbing is the thought that it separates the contemporary West from its peers. Otto Ohlendorf and the regime he served did all they could to conceal their deeds from Western eyes. Nazi Germany still operated in a West founded on Enlightenment values. So massive a violation of a shared patrimony needed to be hidden from view.

In contrast, Hamas initially sought to publicize its deeds, assuming they would win applause, admiration, or at least tacit acceptance in the Arab and Muslim worlds. Here they succeeded beyond their expectations. The many millions who don’t share the West’s patrimony, and who know next to nothing about the Holocaust or Nuremberg, do see things as Khalidi says they see them. (So, too, does a sliver of alienated opinion in the West, where such views are cultivated and celebrated.)

Finally, and still more disturbing, is the fact that Ohlendorf’s defense has been revived to frame the massacre of Jews. Let’s be clear: this isn’t a world war. October 7 isn’t the Holocaust continued: in three months of 1942 alone, on average, the Nazis killed more than

ten times the amount of Jews killed on October 7, every single day (Operation Reinhard). And Gaza is not Dresden, Hamburg, Pforzheim, Kassel, or any of the other German cities bombed so intensively that they literally burst into flames. The Israel-Hamas war is a skirmish by comparison.

But the Ohlendorf and Hamas defenses are the same, and so is the identity of their victims. That’s why it’s important that Israel take some of the Hamas masterminds alive, and place them on trial, Nuremberg-style. Israel owes it to the dead and wounded, their families, all Israelis, and all Jews. But it’s the Arabs and Muslims who most need to see the evidence, hear the testimonies, and weigh the arguments. No part of the world is further from drawing the line drawn at Nuremberg. October 7 is the place to start.

You must be logged in to post a comment.