Exactly 200 years ago, a disturbing painting debuted in Paris, depicting a massacre in a distant corner of the Mediterranean. No other work in the artistic canon speaks more to the events of October 7 than this one.

The painting Scenes from the Massacres of Chios by the French artist Eugène Delacroix was first unveiled at the Salon, the exhibition that defined artistic taste in 19th-century Paris, on August 25, 1824. For the past 150 years, it has belonged to the Louvre Museum in Paris. Millions have seen it over two centuries, and critics, art historians, and Delacroix biographers have analyzed it from every possible angle.

My purpose is more personal than theirs. For myself—and, I imagine, for many of my fellow Israelis, Jewish co-religionists, and friends of both—this painting cannot but evoke the primal brutality of October 7. I’ve attended a few exhibitions in Israel that attempt to capture October 7 in art. Contemporary sensibilities, along with the Israeli modernist tradition in art, permit this only at a high level of abstraction. By contrast, Delacroix’s painting is visceral. Indeed, it’s reminiscent of the horrific videos of slaughter, abduction, and abuse recorded by the body cams of Hamas terrorists.

Death or slavery

The young Delacroix—only 26 when he finished the painting—was inspired by the Greek War of Independence from Ottoman rule, which began in March 1821. “I am thinking of doing a painting for the next Salon on the subject of the recent wars between the Turks and the Greeks,” he wrote to a friend in the fall of 1821. “I think that under the circumstances, this would be a way of distinguishing myself.”

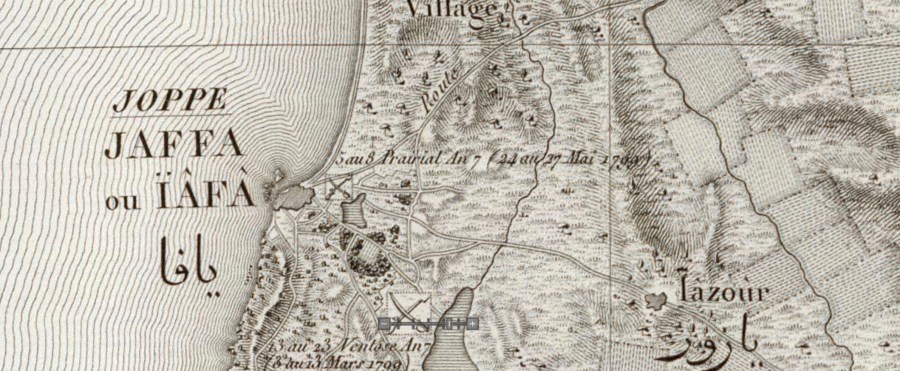

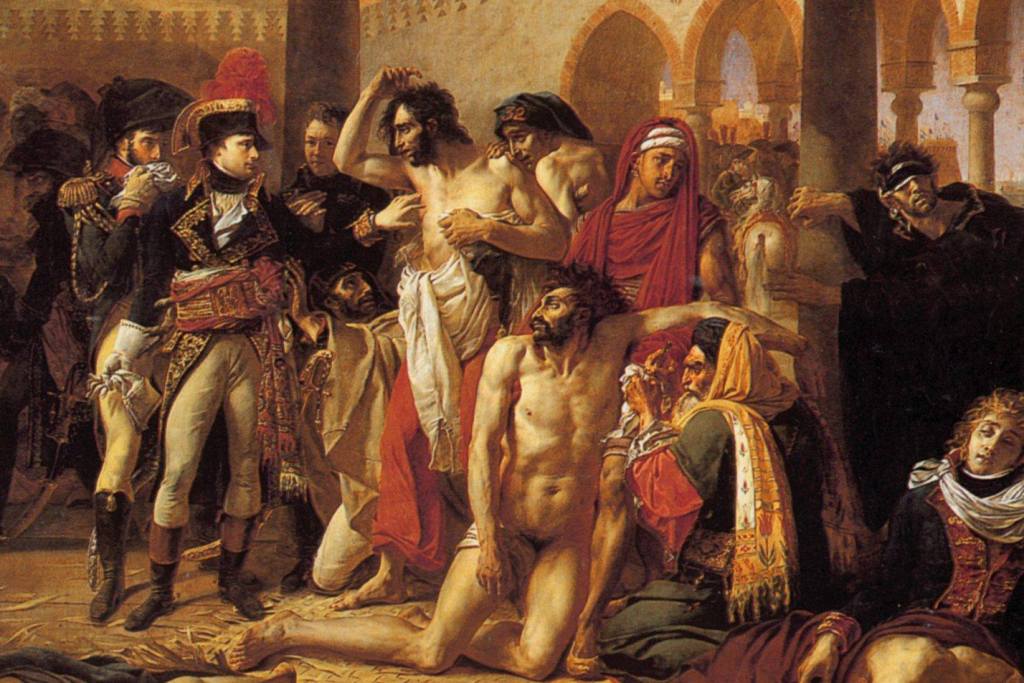

He didn’t complete the painting until the 1824 Salon. Fresh events gave him the impetus. In 1822, the prosperous Ottoman-ruled island of Chios, in the Aegean Sea, was seized by Greek insurgents. The Ottomans recaptured the Greek-populated island with a ferocity that shocked Europe. Estimates vary, but the Ottomans massacred, enslaved, and starved as many as 100,000 Greek Christians, leaving the island depopulated. Graphic accounts of savage torture spread across the continent, fueling the philhellene movement with rage and resolve. In composing his painting, Delacroix relied on such reports, as well as conversations with a French eyewitness.

The subtitle of the work as submitted was “Greek families await death or slavery, etc.,” with the “etc.” serving as a discreet allusion to rape. The painting is centered on a cluster of despairing men, women, and children. Defeat, degradation, and resignation are etched on their faces. The most poignant tableau rises on the right side of the painting: a naked, bound woman is being dragged away by an indifferent Turkish horseman, destined for rape and slavery. Beneath lies the corpse of a dead mother, while her living infant instinctively searches for her bare breast. The bodies of Greek wounded and dead are strewn across a scorched and devastated landscape, where a battle still rages. The impact of the work is magnified by its overwhelming size: the painting is nearly fourteen feet high (over four meters) and almost twelve feet wide (over three meters). It hangs today in the gallery reserved for the largest masterpieces.

It was an unconventional work. The painting referenced contemporary events, not classical history. Delacroix did not portray his Greeks as ennobled, but as ordinary people. Moreover, the work had no redeeming hero. One contemporary critic found it more evocative of a plague scene than a massacre. Art historians have also offered their interpretations. Is the painting a subversive critique of the French regime’s neutrality regarding Greek independence? Is it Islamophobic, positing Islamic barbarity against Christian civilization? Or is the depiction of the Turkish horseman, indistinguishable from a Greek, a deliberate challenge to prejudice?

In an art history seminar, these questions all have their place. But this is a painting that has always stirred emotions and invites analogies. Many could be drawn; the intervening 200 years provide plenty.

Historical continuities

The foremost French specialist on Islam and politics, Gilles Kepel, in his new book Holocaustes: Israël, Gaza et la guerre contre l’Occident, has presented October 7 through the lens of its perpetrators, as a ghazwa (razzia in European parlance): a raid deliberately intended to subjugate and dehumanize a non-Muslim adversary. The Prophet Muhammad conducted such a raid against the Jewish tribes of the Khaybar oasis in Arabia in the year 628, establishing the ghazwa as a model of warfare that would be replicated throughout history. At Khaybar, writes Kepel,

cruelty was explicitly embraced as an exemplary punishment of God’s enemies. Men were tortured and put to the sword, women were captured and distributed among the victors’ harems, and children were enslaved, all to the cries of ‘O Victorious One, bring death, bring death!’ (Ya mansûr! Amit, amit!). On October 7, there was an attempt to emulate this feat from sacred history with the ruthless massacre of Jews, the abduction of women and children from border kibbutzim and the attack on ‘the tribe of Nova.’ Videos circulating online showed prisoners being assaulted, paraded as trophies in jeeps, unfortunate women stripped naked on pickup trucks and perched on motorcycles to be transported to Gaza’s tunnels—just as the captives of Khaybar were once carried off on camels.

The line that connects the years 628 and 2023 (with 1824 along the way) is one of traditionally Muslim and now Islamist supremacism. It not only promises victory but seeks to inscribe it upon the bodies of the vanquished.

We cannot bear to see or hear this, which is why the most graphic images and testimonies from October 7 are still withheld. Delacroix, for all the emotion and outrage he wished to stir, likewise did not depict the full extent of the brutality on Chios. But Scenes from the Massacres of Chios came as close as Western art dares. That this canvas from another era still speaks to our moment is a reminder of continuities we would rather forget.

You must be logged in to post a comment.