Ann (Nancy) K.S. Lambton, the distinguished British historian of medieval and modern Iran, died on July 19 at the age of 96. Her obituaries tell some of her remarkable story as a pioneering scholar and a formidable personality. They are also interesting for what they omit, regarding her role in the idea of removing Mohammad Mossadegh from power in Iran.

Ann (Nancy) K.S. Lambton, the distinguished British historian of medieval and modern Iran, died on July 19 at the age of 96. Her obituaries tell some of her remarkable story as a pioneering scholar and a formidable personality. They are also interesting for what they omit, regarding her role in the idea of removing Mohammad Mossadegh from power in Iran.

The Independent obit says nothing. The Times obit makes an all-too-brief allusion: “She was consulted by British officials on developments in Irano-British relations, especially during the crisis in 1951 when Iran’s Prime Minister, Muhammad Mussadiq, caused a furore by nationalising British oil interests in Iran.” Yet we are not told exactly what she proposed in these consultations. The Telegraph is more explicit: “Lambton’s insights into the strengths and weaknesses of Iran’s then prime minister, Mohammed Mossadegh, proved a valuable aid to Britain’s eventual success, in concert with America, in precipitating an end to Mossadegh’s premiership and in ensuring a continued, though reduced, British share in Iran’s oil production.” Yet we are not told just how she imparted these “insights,” or why they were “valuable.” The Guardian quotes a historian as saying her advice “marked the beginnings” of the 1953 coup, but does not explain what she advised or how she had such a profound effect. So what is the fuller story behind these allusions?

In 1951, Ann Lambton was a Reader in Persian at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. She had many connections in Whitehall, and her standing as an oracle on matters of Persian politics was unassailable. She had completed her doctorate in 1939 after a year of field work in Iran, and then spent the war years as press attaché in the British Legation (later Embassy) in Tehran, under the most seasoned of old hands, Sir Reader Bullard. She also came from a prominent landed family with assorted estates (including, yes, a Lambton Castle)—an advantage of pedigree that largely made up for what still was, in those days, a gender deficiency. When Nancy Lambton spoke, people listened—and when it came to Mohammad Mossadegh, she had strong views.

The historian Wm. Roger Louis first went through the British archives on the Mossadegh affair just after they were opened in the early 1980s, and he has told the story three times, in two books and an article (most recently here). “Here the historian treads on patchy ground,” warns Louis. “The British archives have been carefully ‘weeded’ in order to protect identities and indeed to obscure the truth about British complicity.” But he came across the minutes of conversations between Lambton and a Foreign Office official who described her as someone who knew Iran “better than anyone else in this country.”

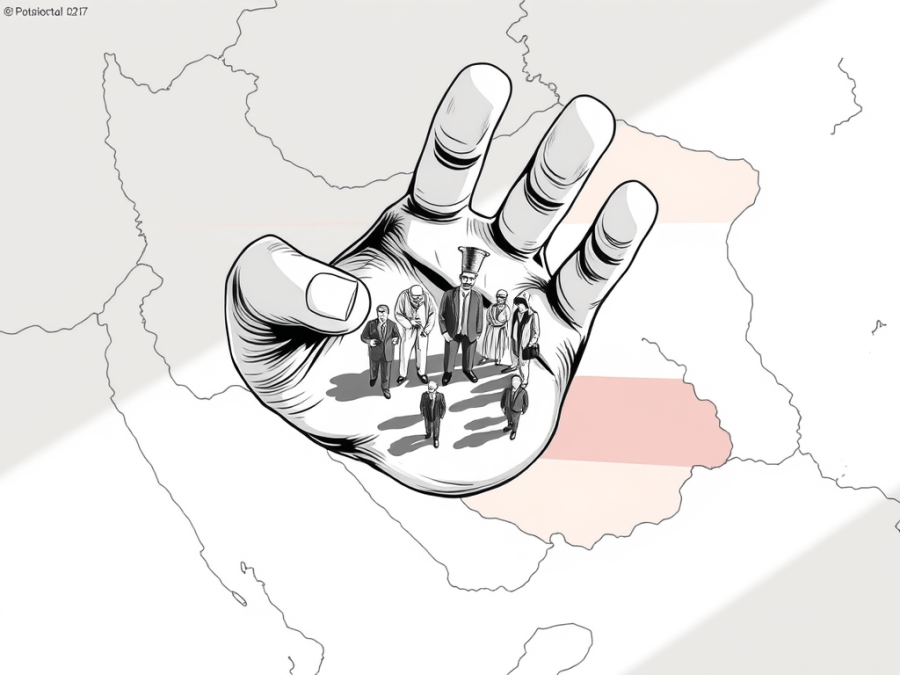

Lambton, the official reported in June 1951, “was of the decided opinion that it was impossible to do business” with Mossadegh, and that no concessions should be made to him. She urged “covert means” to undermine his position, consisting of support for Iranians who would speak out against him, and stirring opposition to him “from the bazaars upwards.” The official added: “Miss Lambton feels that without a campaign on the above lines it is not possible to create the sort of climate in Tehran which is necessary to change the regime.” He then relayed her practical recommendation: entrust the mission to Robert (Robin) Zaehner, a quixotic Oxford don and former intelligence agent, fully fluent in Persian, whom Lambton described as “the ideal man” for the job. On Lambton’s recommendation, the Foreign Office dispatched Zaehner to Tehran, where he put together a network of disaffected opponents of Mossadegh’s regime.

This effort came to naught, partly because the Truman Administration still thought the British should deal with Mossadegh. In November 1951, Lambton complained: “The Americans do not have the experience or the psychological insight to understand Persia.” But she did not relent: “If only we keep steady, Dr. Mossadegh will fall. There may be a period of chaos, but ultimately a government with which we can deal will come back.” Anthony Eden, Foreign Secretary, added this note: “I agree with Miss Lambton. She has a remarkable first hand knowledge of Persians & their mentality.”

Yet Mossadegh hung on, and a year later he shut down the British diplomatic mission. According to Lambton’s Foreign Office contact, she thought that the British policy of not making “unjustifiable concessions” to Mossadegh “would have been successful had it not been for American vacillations,” and she insisted that “it is still useless to accept any settlement” with Mossadegh, “because he would immediately renege.”

This was the prevailing British view, and persistence ultimately paid off. In November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was elected U.S. president, and the new team in Washington took a very different (and dimmer) view of Mossadegh. Anthony Eden met with the president-elect to discuss “the Persia question,” and the CIA’s Kermit Roosevelt and Donald Wilbur set in motion the wheels of the August 1953 coup—an American-led, joint CIA-MI6 production.

“In that [first] minute [of June 1951],” writes historian Louis, “may thus be found the origins of the ‘Zaehner mission’ and the beginnings of the 1953 coup.” Louis asserts that “the archives, for better or worse, link Professor Lambton with the planning to undermine Musaddiq.” He notes that “Lambton herself, as if wary of future historians, rarely committed her thoughts on covert operations to writing. The quotations of her comments by various officials, however, are internally consistent and invariably reveal a hard-line attitude towards Musaddiq.”

In the latest 2006 retelling of the tale by Louis, he has somewhat trimmed his estimate of Lambton’s role. “I have the impression from the minutes,” he writes in a footnote, “that the officials quoting [Lambton] sometimes wanted to invoke her authority to lend credibility to their own views.” Louis also adds that Lambton’s “views were entirely in line with those of other British authorities on Iran.” In other words, she was urging them to think or do something they already thought or wanted to do anyway, but for which they needed an authoritative footnote.

But there can be no doubt that her advice bolstered the advocates of toughing it out and bringing Mossadegh down. The obits tend to downplay this story because the 1953 coup has come to be seen as some sort of original sin—as the root cause of the Islamic revolution that unfolded a full quarter-century later. But wherever one puts the 1953 coup in the great chain of causation, Lambton’s assessments at the time should inspire awe. Years of experience in Iran, exact knowledge of Persian, and wide travels within the country, all had led her to conclude that Mossadegh could be pushed out, as against the view that he had to be accommodated. She was right. Given the propensity of Western experts on Iran to get so many things wrong over the years, Lambton’s call is all the more remarkable.

The present incumbents in power in Iran are careful to shut out Western Orientalists, not because they fear the situation in Iran will be misrepresented but because it might be accurately represented, exposing the weaknesses of their regime. The historian Ervand Abrahamian, mentioning Lambton (and Zaehner), writes that it should not be surprising that the coup “gave rise to conspiracy theories [among Iranians], including cloak and dagger stories of Orientalist professors moonlighting as spies, forgers, and even assassins. Reality—in this case—was stranger than fiction.” The reality is that it isn’t easy to hide one’s vulnerabilities from an intimate stranger such as Lambton. The fear of Orientalist professors, both there and here, has never been that they might get things wrong, but that they are very likely to get them right.

Originally posted at Middle East Strategy at Harvard.