This year, 2023, marks two significant anniversaries: the twentieth anniversary of the 2003 Iraq War and the fiftieth anniversary of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The commemorations of these two anniversaries unfolded on two parallel tracks, which never intersected.

The reason for this divergence is not hard to understand. What common ground could they possibly share? The 1973 war began with a surprise attack by two Arab states against Israel, aiming for limited political objectives. In contrast, the Iraq War was a well-telegraphed American offensive against Iraq, undertaken with the ambitious goal of regime change.

If we draw parallels between Israel and the U.S., then Israel found itself caught in an unwanted war, while the U.S. actively initiated a war it desired. When comparing Egypt and Syria with Iraq, the former launched the offensive, whereas Iraq played a strictly defensive role. The 1973 war involved local Middle Eastern states in conflict, whereas the Iraq War saw the world’s sole superpower confronting an Arab state.

At first glance, drawing comparisons between the wars of 1973 and 2003 might appear unlikely to yield any meaningful insights. However, I wish to attempt the comparison anyway, as there are some underlying similarities that may be relevant to a broader spectrum of conflicts. These parallels could offer lessons for the future, although it’s well-known that deriving practical lessons from history is a perilous proposition.

Past as precedent

The first similarity is that both wars were influenced by earlier conflicts in which Israel and the United States emerged victorious. Israel’s Six-Day War in 1967 resulted in a swift and decisive victory, bringing large Arab territories under its control. Similarly, the United States’ Gulf War in 1991 was a clear win, with the U.S.-led coalition easily liberating Kuwait from Iraqi occupation.

These swift and relatively easy victories bred a sense of exaggerated self-confidence, bordering on hubris, among the victors. In Israel’s case, this led to the belief that no sane Arab state would dare attack it after the humiliating and comprehensive defeat they suffered in 1967. For the U.S., the ease of victory in 1991 fostered the expectation that Iraqis wouldn’t fight back against occupation. These assumptions set up Israel for the shock of the combined Egyptian-Syrian attack and the U.S. for the unanticipated Iraqi insurgency.

Intel and bias

A second similarity involves intelligence failures, rooted in a reluctance to acknowledge information that contradicted the prevailing narratives about the enemy. In Israel’s case, signs of Egyptian and Syrian war preparations were interpreted away as the intelligence assessments ascended the chain of command. Only at the last minute did incontrovertible evidence reach the decision-makers, but by then it was already too late.

In the Iraq case, a similar selective perception led to the exaggeration of unreliable reports about Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction. It was only after the U.S. invasion that the reality became apparent: Iraq did not possess such weapons. In both instances, Israel and the U.S. were misled by deception campaigns: Egypt and Syria fooled Israel into believing their war preparations were just exercises, while Saddam Hussein misled the West into thinking he possessed WMD. (He was under the mistaken belief that such weapons would deter an attack against Iraq.)

Both intelligence failures underwent scrutiny in post-war analyses, which arrived at similar conclusions: preconceived biases had distorted the analysis of the collected information. As a result, Israelis overlooked actual threats, while Americans perceived threats that were non-existent.

Tainted victory

A third similarity is the perception of failure despite achieving military victory. Israel arguably secured its greatest military triumph in the 1973 war: it swiftly repelled and encircled the enemy on both fronts, ending the conflict with more territory than at its outset. Yet, the 1973 war is remembered as a low point in Israeli history, its successes overshadowed by the initial surprise attack and the high number of Israeli casualties.

Similarly, the Iraq War is perceived by many in America as a strategic failure. Despite the U.S.’s rapid overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime and the subsequent “surge” that curbed the insurgency, the conflict led to a prolonged and costly occupation, inadvertently strengthened Iran’s position in the region, and contributed to the emergence of ISIS.

The political price

This leads to the fourth similarity: both wars had profound consequences for the politics of Israel and the U.S. In Israel, the 1973 war eroded public confidence in the Labor party, ending its quarter-century of dominance. In the U.S., the Iraq War and its aftermath deeply polarized public opinion, undermining the Republican establishment along with its neoconservative wing, and spurred a reevaluation of America’s role in the world.

The effects in both cases were not immediate. Despite the public disaffection over the 1973 war, the Labor party under Golda Meir won the parliamentary election two months later, with the government lasting until 1976. (Meir herself resigned from the prime ministership in 1974, succeeded by Yitzhak Rabin.) Similarly, George W. Bush was reelected in 2004, continuing his presidency for another four years.

However, in the longer term, the wars significantly undermined the standing of both Meir and Bush. When historians and experts are surveyed, these leaders frequently rank in the bottom third among prime ministers and presidents, respectively. Moreover, the wars set the stage for the ascendancy of outsiders (and outliers) from the opposition: Menachem Begin in 1977 and Barack Obama in 2008.

Painful reassessments

The fifth similarity lies in how Israel and the United States reassessed their approaches to the Arab world following each war, albeit in opposite directions. Prior to the war, Israel had favored maintaining the status quo, valuing the certainty of territorial control over the uncertainties of peace. The war, however, convinced Israel that peace, even if it required territorial concessions, could bolster its security.

Conversely, the United States had been inclined to break the status quo in pursuit of a “freedom agenda” and the promotion of democracy. The Iraq War and its aftermath led America to conclude that the risks of this approach far outweighed its potential benefits. The 1973 war diminished Israel’s pessimism about peace, while the Iraq War dampened American optimism about promoting democracy. Both events became significant conceptual watersheds.

What’s to be learned?

The lessons drawn from these similarities might seem obvious. Indeed, wars often stem from hubris, particularly the belief that past military successes can be easily replicated. Intelligence failures frequently serve as a prelude or even a necessary condition for war. It’s possible to achieve a military victory yet still feel as though the war was lost. Wars can significantly reshuffle domestic politics, especially when the costs are perceived as excessively high. And certainly, wars prompt the overhaul of previous strategies, necessitating reassessments. These truths apply not only to the wars of 1973 and 2003 but also to many other conflicts that did not share an anniversary this year.

But are these lessons ever truly learned? We find ourselves in the midst of another war in the Middle East, between Israel and Hamas. Already, the initial similarities are evident: Israel lowered its guard, basing its confidence on previous rounds with Hamas which supposedly left Hamas deterred; meanwhile, intelligence, filtered through biases, rendered Israel blind.

And it’s likely that we’ll soon witness the rest unfold. Israel will prevail militarily, but its people already perceive the Hamas war as a new low point. The nation’s political and military leaders likely will pay a steep price for perceived failures. And there will probably be a reassessment of the strategy that aims to bypass the Palestinians entirely in the pursuit of regional peace.

These similarities have yet to fully materialize. Perhaps I’ll revisit them in 2033, when we will be marking not just two, but three war anniversaries.

From a roundtable discussion marking the Iraq War anniversary, annual conference of the Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa (ASMEA).

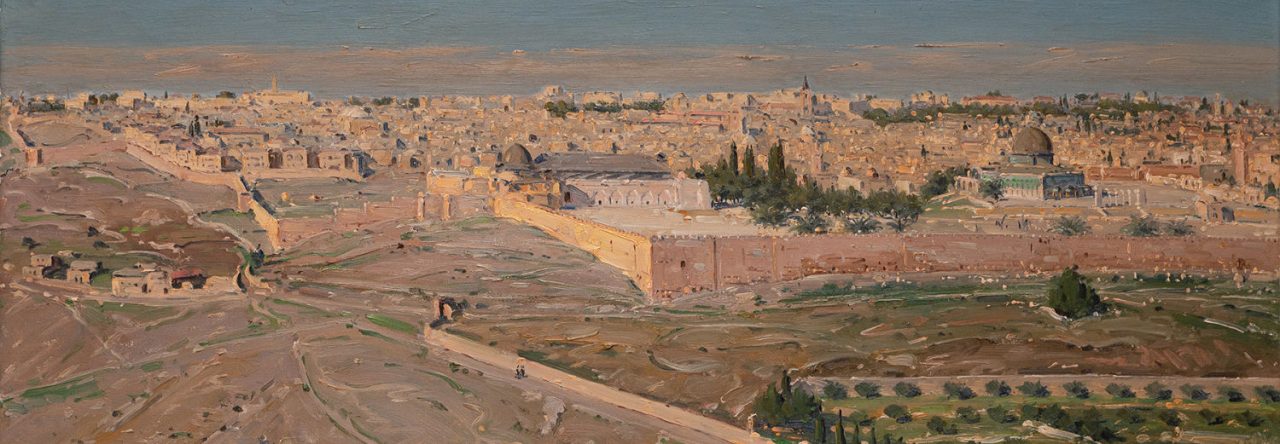

Header image created by DALL-E, OpenAI’s image generation model.

John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt

John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt

You must be logged in to post a comment.