“When newly-appointed Professor of Near Eastern Studies Bernard Lewis arrives in Princeton next Wednesday, his presence will make the university ‘the strongest school in Near East history in the country.’” Thus did the Daily Princetonian report Lewis’s arrival, expected on Wednesday, September 11, 1974, fifty years ago today.

The migration of historian Bernard Lewis from London to Princeton, and from Britain to America, changed the lives of many students, myself included. By some accounts, it changed the role of the United States in the Middle East. Whether it did so is a larger question for another time. But how the move came about is a smaller story worth telling in its own right, and on this anniversary, I’ll share just a bit of it.

Brain drain and gain

In the years following the Second World War, many British academics made the transatlantic move, accepting positions at American colleges and universities. It was a case of both push and pull. The war had left British higher education strapped for funds, while American academia was booming, fueled by the federal government and major foundations. The resources of Oxford or London paled in comparison to those of Harvard or Yale.

In 1961, an official British inquiry into the state of area studies (the Hayter Committee) painted a grim picture of “the drain of manpower to America”:

Scholars overseas are already receiving tempting offers from American universities…. The pressure on Great Britain has started and several key university teachers have now left for America. Recently 12 members of the staff of the School of Oriental and African Studies were under offer from American universities… At present the lure of posts in America arises as much from the better amenities, the larger libraries and the more generous funds for travel as from the cash salaries.

During these years, American universities expected their foreign recruits to be institution-builders, since so much had to be constructed from scratch. A prime example was Sir Hamilton Gibb, Lewis’s teacher, who in 1955 traded a chair of Arabic at Oxford for one at Harvard. At the age of 60, he assumed a heavy burden of teaching, administration, and fundraising. The general consensus was that Gibb did not succeed at Harvard; even an admirer admitted that “his administrative arrangements did not always have the results he intended.” While he mentored some notable students, he built nothing lasting and his research agenda suffered. “His own work had to be done in the intervals of teaching, administration, and acting as elder statesman.”

Lewis may have inferred from this precedent that an American appointment could lead to frustration. Or he may have had other commitments he was unwilling to stretch or sever. Regardless, while others left, he stayed. “The drain of key people to America,” noted the 1961 report, “is already severe in some places, particularly at the School of Oriental and African Studies” (SOAS), where Lewis taught. But it didn’t include him. Yes, he received feelers from American universities, but he only pursued them for the occasional visiting professorship. In Britain, researchers coined a term for this: “brain circulation” (as opposed to outright “brain drain”). Lewis completed stints at UCLA, Columbia, and Indiana.

Lewis likely never would have migrated to America if not for his own specific push and pull factors. The push was a difficult divorce that left him demoralized and financially strained. (He wrote about this in some detail in his memoirs.) The pull was the deal that brought him over. Unlike Harvard’s arrangement with Gibb, the agreement with Lewis set him up for success, by supercharging his productivity.

That’s because the offer to Lewis came not only from the university, but also from the Institute for Advanced Study. Although located in Princeton, the Institute is entirely separate from the university, with a distinct mission: to encourage a small number of scholars to focus exclusively on pure, undistracted research. The Institute has no students, classes, or degree programs.

After some maneuvering by academic allies, Lewis received offers from both the university and the Institute, each for a half-time position. It was a major coup for Avrom Udovitch, new chairman of the Near Eastern Studies department at the university, and Carl Kaysen, director of the Institute. They faced a question evocative of quantum physics, a field in which the Institute excelled: could someone be in two places at once? Some Institute faculty had their doubts. In the past, such dual appointments, though rare, had been “more advantageous to the University than to the Institute,” according to skeptics.

But the deal went through. Lewis’s supporters at the Institute reassured the doubters, and Philip Klutznick, a Chicago real estate developer, stepped in to fund the Institute’s share. One of the peculiarities of the dual arrangement was Lewis’s title at the Institute: “Long-term Member.” Had he been full-time, he would have held the title of professor. At the university, however, he became the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor of Near Eastern Studies.

In his memoirs, Lewis explained the advantages of the arrangement:

Thanks to my joint appointment I had to teach only one semester; the rest of my time was free of teaching responsibilities, except of course for the supervision of graduate students preparing dissertations…. A second advantage was that being a newcomer from another country, I was free from the kind of administrative and bureaucratic entanglements that had built up, over decades, in England. This was a most welcome relief.

The late Robert Irwin, one of Lewis’s London students, recalled that his position at SOAS “necessarily also involved him in teaching, supervising, editing, seeking funds, launching programs, and so forth.” The Princeton arrangement dramatically reduced that burden. Lewis emphasized that it gave him “more free time” to focus on research and writing.

In the month after Lewis arrived in Princeton, he spoke to the Daily Princetonian, describing his dual arrangement as “a way of having one’s cake and eating it too.”

Leisure, space, privacy

I was an undergraduate senior when Lewis arrived that September. He wasn’t offering a course at my level, and I only recall glimpsing him in Jones Hall, home of the Near Eastern Studies department. In retrospect, I’m surprised I didn’t seek him out. But at the time, the department didn’t accept its own undergraduates for graduate study, so I planned to leave. It was Udovitch who pulled me aside and told me that if I left for a year, I’d be eligible to return.

By the time I returned in the fall of 1976, Lewis had become a fixture at the university, and I enrolled in his graduate course on Arabic political vocabulary. At some point, he invited me to visit him at his Institute office, where I witnessed the great advantage he enjoyed through his dual appointment.

Lewis sat atop Olympus. The Institute, removed from the university, sat within an 800-acre park with its own woods. He occupied a gleaming white office the size of a large studio apartment, housed in a striking modernist building. The office featured a work area and a lounge, with windows running its length. Much of his enormous library lined the walls. The Institute, Lewis wrote in his memoirs, “gave me leisure, space, and privacy, all three of them, especially the latter, in ample measure.” Privacy, indeed: here he could work completely undisturbed, far from the nosy faculty, noisy students, and annoying tourists who crowded the campus.

I came to know that office very well. Not only did I visit Lewis, who became my dissertation adviser, for afternoon tea and walks in the woods. He also hired me to catalog incoming offprints and gave me the office key. I spent many evenings and weekends there while he was elsewhere, sitting at his desk, organizing the offprints, doing my own research in his library, and occasionally sneaking a glance at his opened mail.

It was at this desk that he wrote a famous series of Commentary articles that transformed him into a major public intellectual. They included “The Palestinians and the PLO” (1975) and “The Return of Islam” (1976). It was also here that he wrote “The Anti-Zionist Resolution” for Foreign Affairs (1976), and “The Question of Orientalism,” his rejoinder to Edward Said, for the New York Review of Books (1982).

His scholarship also flourished. In quick succession, he authored History—Remembered, Recovered, Invented (1975), The Muslim Discovery of Europe (his major work of this period, 1982), The Jews of Islam (1984), Semites and Anti-Semites (1986), The Political Language of Islam (1988), and Race and Slavery in the Middle East (1990). Each article, book, and controversy propelled Lewis still further into the American limelight, paving the way for his eventual emergence as a post-9/11 sage.

Decade after decade

The university had a mandatory retirement age of 70, and Lewis’s retirement in 1986 automatically triggered his departure from the Institute. Had he done nothing more, his brief American epilogue would still have been considered a stunning success.

But two other factors came into play, neither of them predictable. First, Lewis defied the actuarial tables, remaining healthy and energized well into his nineties. Second, the Middle East continued to produce new surprises every decade, pulling America ever deeper into the region. This began with the Iranian Revolution in 1979, before Lewis’s retirement, and continued afterward with the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the 9/11 attacks in 2001. After each shock, American policymakers and the public sought context and guidance, which Lewis provided in abundance.

Had Lewis not made the crossing in 1974, his voice might still have been heard in America, but it would have been distant and faint. His decade-plus in that splendid Princeton office transformed him from a British don into an American public intellectual, with a reach extending from network studios to the White House.

Small decisions often have outsized and unintended consequences, affecting both the careers of individuals and the history of nations. I submit that this one, made by the faculty of the Institute for Advanced Study in late 1973, deserves far more recognition than it has received:

The Faculty takes note of the proposal of the School of Historical Studies concerning Bernard Lewis as forwarded to it in the letter of the Director and will welcome the presence of Bernard Lewis at the Institute.

The motion was seconded and passed unanimously.

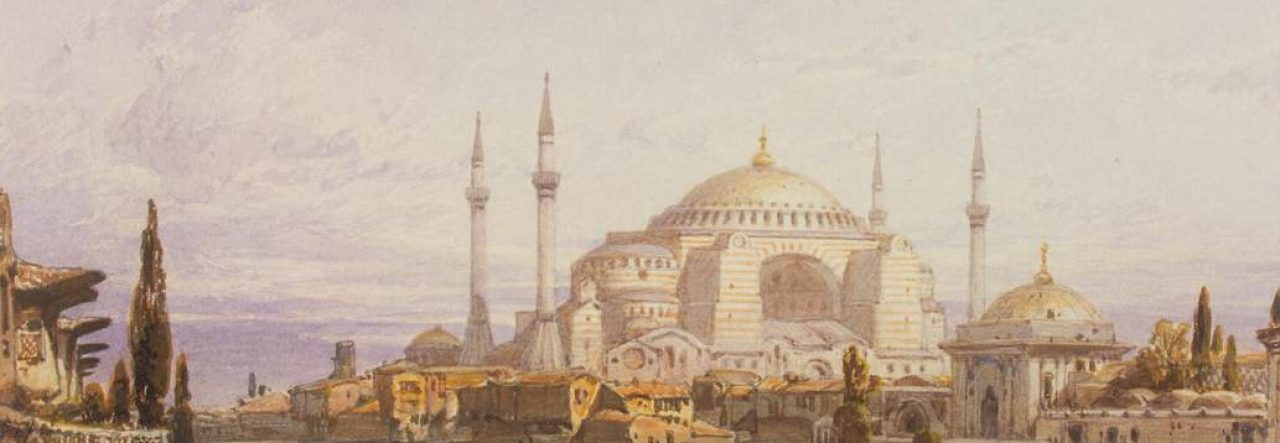

Header image: Fuld Hall, The Institute for Advanced Study, Wikimedia Commons.

You must be logged in to post a comment.