This past Sukkot holiday marked an important anniversary for the National Library of Israel and the study of Islam in Israel. A century ago, the Hebrew University opened a prized acquisition to the Jerusalem public: the 6,000-volume private library of Ignaz (Isaac Jehuda) Goldziher, the Jewish-Hungarian scholar of Islam. The books had been transported from Budapest, after lengthy negotiations and at some cost. Chaim Weizmann welcomed their arrival, addressing an enthusiastic crowd of Jews, Christians, and Muslims outside the library. Jerusalem’s British governor and Arab mayor also attended.

The accession of Goldziher’s library marked a triumph for the Hebrew University. Several generations of students and scholars would rely on the collection to maintain their competitiveness with the highest research standards. This centennial offers an opportunity to remember Goldziher and reflect on the journey and impact of his books.

Making of a master

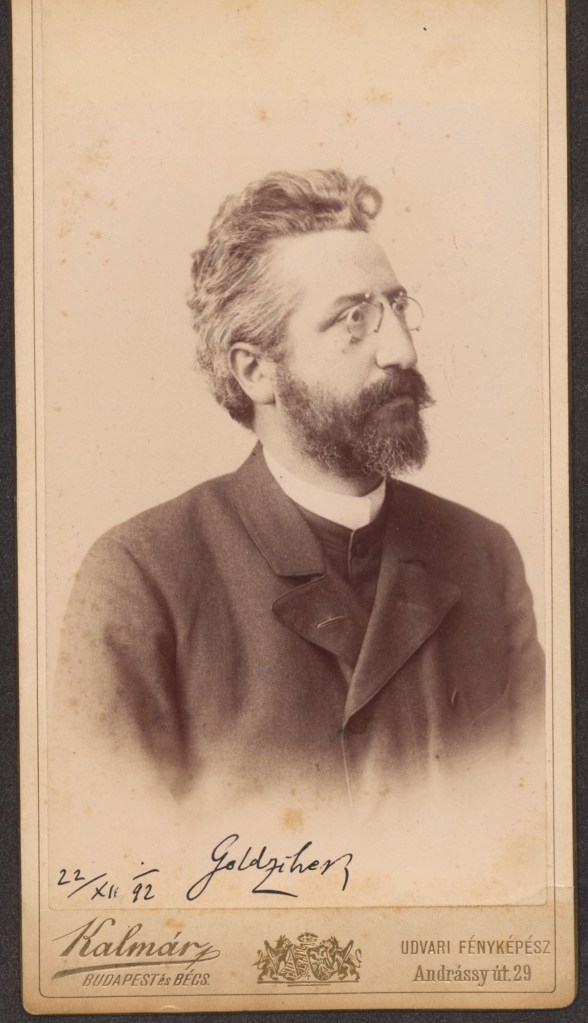

“The Great Goldziher,” as admirers called him even during his lifetime, laid many of the modern foundations for scholarly Islamic studies. Born in the Hungarian town of Székesfehérvár to the son of a leather merchant, he received rigorous schooling in the Hebrew Bible and Talmud from an early age. He completed his philological studies in Leipzig in 1870, and then traveled further through Europe and the East. He even studied at Cairo’s famed Islamic university, Al-Azhar.

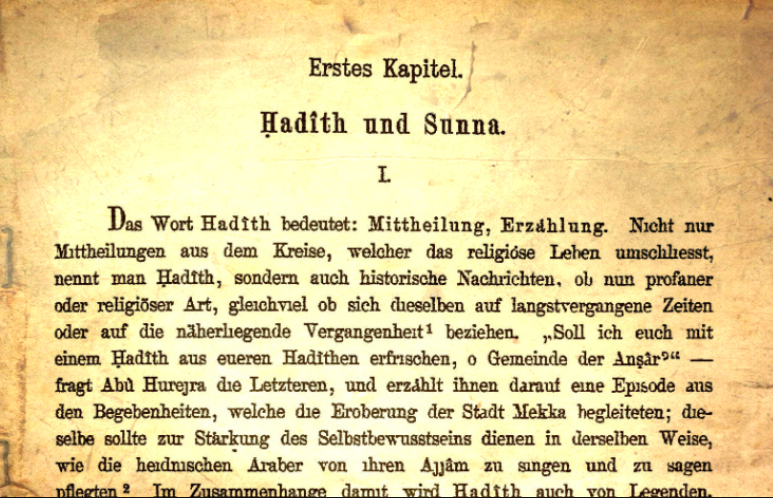

Goldziher’s Jewish faith precluded a professorship at the University of Budapest, and from 1876 he earned a living as secretary to one of the Jewish communities in the city. Only in 1905, at the age of 55, was he finally appointed to a salaried chair at the university. This meant that Goldziher had to pursue his studies on Islam after hours, following long days spent on menial tasks that he detested. His interests ranged widely, from the development of Muslim sects to Arabic poetry. But his most renowned contribution was his study of Islam’s oral tradition, the hadith, which he viewed not as a record of the Prophet Muhammad’s deeds and sayings, but as a window into the first centuries of Islam.

In the 1890s, as Goldziher’s reputation grew, foreign universities such as Heidelberg and Cambridge attempted to recruit him. But he refused to leave Hungary for personal and patriotic reasons. Nor did he consider relocating to Palestine. Goldziher, while an observant Jew, was not a Zionist. In 1920, his old schoolmate, the Zionist leader Max Nordau, encouraged him to join the planned university in Jerusalem—the future Hebrew University. Hungary had just fallen under the rule of Admiral Horthy, whose regime enacted sweeping antisemitic policies, including strict quotas on Jews in higher education. Goldziher declined Nordau’s proposal: “Parting with the [Hungarian] fatherland, especially at this time, would demand a heavy sacrifice from a patriotic point of view. This is also why I resisted moving to German or English universities in my younger years.”

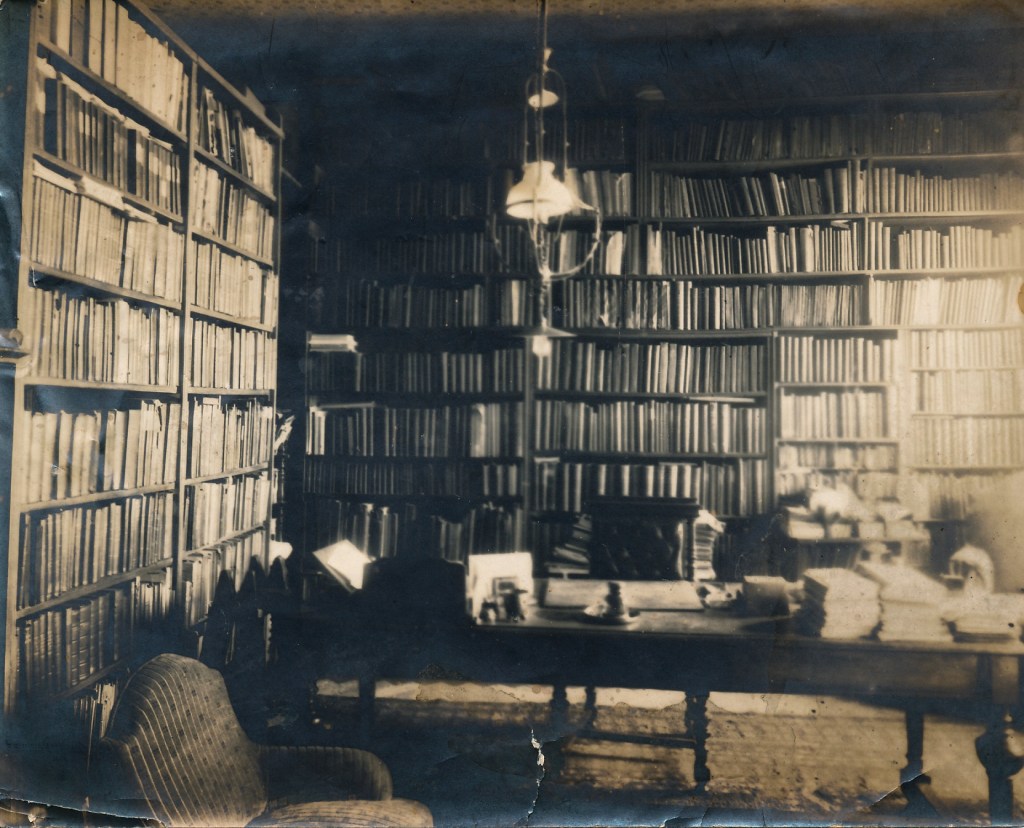

Alongside his research and writing, Goldziher assembled an astonishing private library. Budapest lacked great collections of books and manuscripts from the Muslim East, so Goldziher had to acquire them himself. Foreign visitors to his home were awestruck by the scope of his collection. A young Hungarian rabbinical student, Leopold Grünwald (Greenwald), recalled visiting Goldziher’s home in 1910 and the emotional effect of seeing his library.

The room was his study, a large room filled with several thousand books and hundreds of manuscripts that did not appear to be arranged in any systematic way. Some forty books, for example, large and small, rested on a stool. It was as though a whirlwind had transported me to a Jewish ghetto of several hundred years ago, where the Jew was isolated from the entire world and enjoyed no pleasures except for the four ells of halakhah. Only among his books was he at ease; there alone he found peace. Even the air there was clear of physical desires and pleasures. All was spiritual. I thought to myself, would that I could remain in this ethereal state for as long as I live! Would that I could reject all the vain pleasures and find joy and comfort among books alone!

Floor to ceiling

Goldziher died in November 1921. Lore has it that he wished for his library to go to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, but there is no record that he made any specific provisions for it. His widow and son, pressed for cash, sought buyers, with serious offers coming from as far away as Japan.

However, the most persistent offers came from Jerusalem, where the newly established Hebrew University was eager to expand its library collections to an international standard. The detailed history of the Zionist Executive’s acquisition of Goldziher’s library has been expertly recounted by Samuel Thrope, curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library (here and here). It’s a tale of negotiation, bureaucracy, and competing claims for credit, to which I have nothing to add.

Instead, I’ll share the vivid account of Israel Cohen, the British Zionist official and journalist who traveled to Budapest to finalize the deal and arrange for the library’s shipment to Palestine. In August 1923, he visited the library in situ, at Goldziher’s home at 4 Holló Street. Cohen described the street as “a long, dreary, narrow thoroughfare, flanked on either side by tall somber buildings, in which the two most homely features are a modest little bethel and a frowsy kosher restaurant.” Remote from “the majesty of the Danube,” Holló Street was “a haunt of unrelieved desolation, where nobody could be expected to dwell by choice; but as the Jewish Community owns Number 4, this has always formed the residence of some of its officials,” of whom Goldziher had been one.

Cohen wondered “what was it that fettered [Goldziher] to this somber dwelling,” when he had received all manner of “luring invitations” and “tempting material prizes” from around the world.

When I first went to visit his home in August 1923, and, later ascending a dim, circular flight of stone steps, found myself on the railed gallery that led to the door, and from which I looked down upon the dirty hand-carts and the rubbish-heaps in the courtyard below and at the lofty, grimy wall opposite, which seemed to shut out the light from heaven, I could not help wondering. For forty-two years, I reflected, this world-renowned savant, from early manhood until his death at the age of seventy-two, was content to tread up and down that dim, stone staircase, pace along the narrow, stone gallery that ran round three sides of the building—the fourth being bounded by the gloomy wall—and live in the humble flat that was entered by a door with chequered and bar-protected window-panes. No more drab and depressing surroundings could be conceived—and to be doomed to such neighborhood for forty-two years! ‘Such is the Torah, and such its reward!’

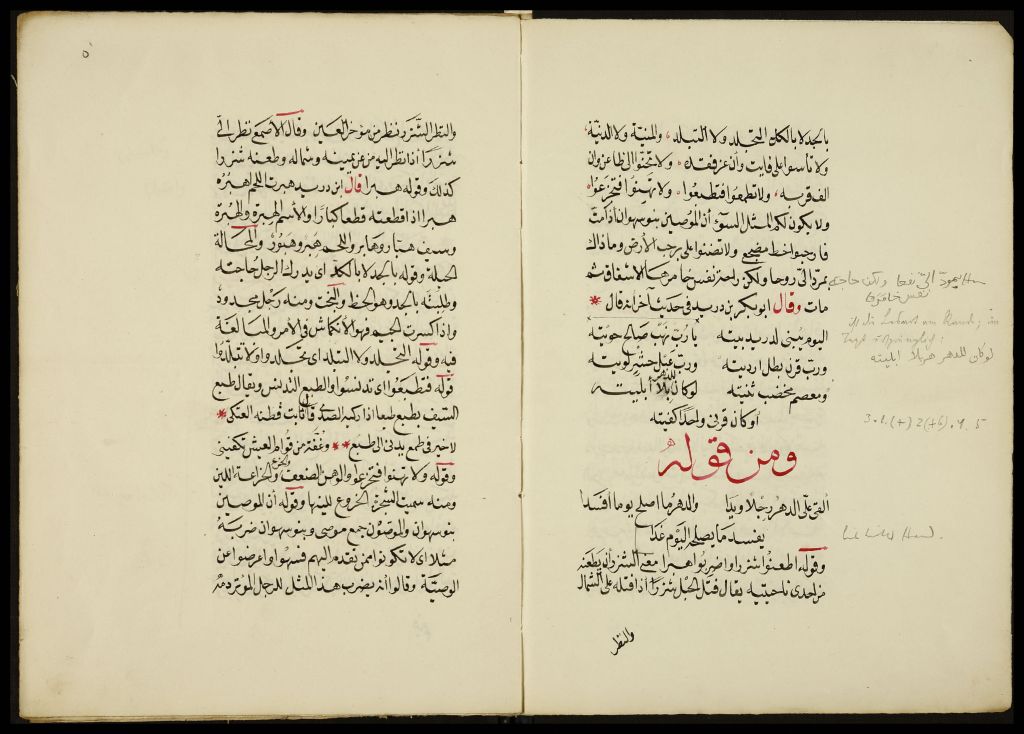

But when I was admitted by the gentle, gray-haired widow, and taken to the room where he had worked, the riddle was solved. For in this room was the wonderful library covering the walls from floor to ceiling and overflowing on to extra shelves, which he had thoughtfully and laboriously gathered together from all the regions of the Near East, and wherein he quarried night and day in quest of new truths. It was his passionate attachment to this library, in and for which alone he lived, that made all the glittering offers from other cities, with their promise of superior ease and comfort, appear but phantasms, and its removal seemed to him unthinkable. Here were arranged the well-thumbed tomes in all the Semitic tongues, which he had either bought or which had been presented to him by their authors or by the erudite societies that published them. The works given by their own writers all contained an inscription of homage and often of gratitude, and not a single Orientalist but considered it a duty and honor to send him a first copy. Many of the books were rare, and those that came from Moslem scholars were probably the only copies on the Continent. And Goldziher enriched most of them with his own notes and glosses, written on the fly-leaves and the margin, or on slips of paper, which form a mine of suggestions for those who will delve into them.

Since Cohen never met Goldziher, he couldn’t possibly have known the scholar’s reasons for staying in Budapest. Still, Goldziher could not have achieved much without his massive library of rare, hand-picked books, and the daunting task of moving them likely reinforced his reluctance to leave. For what it’s worth, Abraham Shapira Yahuda, Goldziher’s mentee and a Zionist, claimed that he had urged Goldziher “to come to the Land of Israel and dedicate the last years of his life to raising a new generation of scholars.” Yahuda regretted that Goldziher “never went to the Land of Israel, partly because he didn’t believe he could bring his books with him.”

For Goldziher’s widow, Laura, parting with her husband’s books was no small thing. Cohen gave this poignant account:

The twenty-two cases were ranged in the library and the adjoining rooms in two rows, between which the frail widow slowly passed, touching each case in turn, as though to retain contact until the last possible moment with the possessions of her husband. They must have seemed to her like coffins, as they were borne out of the dwelling, nor was the sorrow that followed them any less profound than that which accompanies many a real bier. At last they had all been taken away, and she gave a wistful look at the library—bare and desolate. ‘Ichabod—the glory is departed,’ she said, ‘and there is nothing more for me to live for.’

‘The glory is gone from here,’ I replied, ‘to the Holy Land, where it will become more glorious still, and where it will confer an untold blessing by bringing Jews and Arabs together in the peaceful pursuit of scholarship, and thus pave the way to a friendly understanding between the two peoples.’

The following day the Goldziher library was transported to Trieste, whence it was shipped to Palestine.

Books at war

In reports in the Hebrew press about Goldziher’s library, Cohen’s hopeful idea that it might bring Jews and Arabs together appeared frequently. Yahuda was the main promoter of this notion:

Imagine a library where a delightful and wonderful treasure from the finest Arabic literature and key Islamic texts is found. This place could become a center for Arab and Jewish scholars alike, where they would come together as brothers in wisdom and friends in the pursuit of knowledge. The spirit of enlightenment would dwell upon them and inspire our neighbors, who are close to us in both kinship and thought, with the same spirit of tolerance, broad-mindedness, and generosity of soul that once distinguished the Arabs in ancient times.

The poet and writer Kadish Silman attended the opening in Jerusalem, and struck exactly this note:

Besides Jewish scholars and teachers, dozens of English and Arab locals with an interest in scholarship came to the opening. All the editors of Jerusalem’s Arab newspapers were there, as well as the Mufti, the Qadi, and others…. Dr. [Nissim] Malul translated [Weizmann’s speech] into Arabic. The speech made a strong impression. A feeling of unity—and possibly even friendship—was achieved. Afterward, in the library, all the guests from various backgrounds mingled, and Dr. Weizmann gave explanations to everyone. He parted from the Arabs and the English with handshakes and warm wishes. Since we started our local political efforts, never has there been a moment of unity as strong as this one.

Close to the rented Arab house that served as a temporary home for Goldziher’s library, across a rocky expanse, stood a mosque’s minaret. Goldziher’s library had traveled far from Holló Street to fulfill its mission of peace.

Alas, no number of books could have achieved that. In the years that followed, Jews and Arabs collided. Efforts to appoint an Arab to the faculty never bore fruit. In 1936, during the “Arab Revolt,” Lewis (Levi) Billig, the first lecturer in Arabic literature at the Hebrew University, was shot dead at his desk by an Arab assailant. “The manuscript he was preparing,” reported the Palestine Post, “a Concordance of Ancient Arabic Literature, and a large Arabic tome on which he was working, were spattered with blood.” The murder stunned the faculty.

In 1945, the librarian who had organized Goldziher’s collection faced hostility from Arab book dealers in the Old City: “Something like this has not happened to me even in the worst of times.” Then came the 1948 war, when the library salvaged (critics have claimed, looted) as many as 9,000 Arabic volumes from homes abandoned by Palestinian Arabs who fled the fighting. “The number of books brought to the library in this way,” wrote the university’s keeper of Oriental books, “exceeds the number of Arabic books we have gathered over the entire history of the institution.”

Ideas shape history, but the physical books and libraries that contain them have always been subject to its tides.

Spirit and method

The Goldziher collection didn’t change the course of Jewish-Arab relations. But it reached Jerusalem at the right moment, as Israel prepared to establish itself in the face of Arab opposition. By the time Israel gained independence, the Israeli school of Islamic studies was well-established, largely led by scholars who, like Goldziher’s books, had migrated from Central Europe to Jerusalem.

As one such scholar, Martin Plessner, remarked, “Goldziher’s library is one of the most valuable assets of the Hebrew University. His spirit lives among us from the earliest steps of our research into Islam.” But it wasn’t just his spirit that influenced them—it was also his method. “Goldziher used to write many notes in his books,” wrote S.D. Goitein, “especially on the blank pages at the beginning and end of the books. Anyone wishing to see his handwriting and get a glimpse of the working methods of a great scholar need only request an Oriental book printed before 1914 from the library, and they will almost certainly find what they are looking for.” Goldziher’s example, reinforced by the physical presence of his books, set exacting standards for interpreting Islam and Arabic within Israel’s universities, but also far beyond them.

Goldziher’s books are now dispersed throughout the broader library collection. Over the last century, their influence likewise has spread in ways that can no longer be traced—trails left from the big bang that occurred in a drab Budapest walk-up.

THE British historian Robert Irwin is the sort of scholar who, in times past, would have been proud to call himself an Orientalist.

THE British historian Robert Irwin is the sort of scholar who, in times past, would have been proud to call himself an Orientalist.

You must be logged in to post a comment.