Martin Kramer delivered this address to the Shalem Center’s Manhattan Seminar on October 28, 2008.

Good evening. It’s a pleasure to return to the Manhattan Seminar—this is my third appearance here, and it’s always one of the highlights of my autumn stay in the United States. When the date of this meeting was set, back in the summer, it was already clear that the presidential elections would be the point of reference. But no one could know who the candidates would be, and where they would stand in the polls. Today we do know, and unless something unpredictable occurs, Barack Obama will enter the White House as president on January 20. I’m not expressing an opinion here, and certainly not a preference—just a realistic assessment. Of course, presidents are elected by real voters, not by polls, so the battle is still ahead of us. But the writing is on the wall.

To some extent, this makes my assignment more interesting tonight. Originally I intended to give you my own primer on the Middle East, which would have been the same whoever was running for president. But now that we know with reasonable certainty who will be president, it’s much more interesting to wonder what sort of primer he’s already had. And in the case of Obama, as opposed to McCain, the task is especially interesting, because he’s already been given a very bad primer on the Middle East, which he’ll have to unlearn if he’s to have any chance of success in managing this troubled region. So let me begin by discussing the wrongheaded primer that Obama got from some very wrongheaded people.

Let me proceed from the general to the specific. As it happens, I’m very familiar with the way the Middle East is presented in the places where Obama was formed intellectually. He spent a couple of years as an undergraduate at Columbia University in the early 1980s; I myself have a master’s degree from Columbia, which I earned in 1976. He then went on to Harvard Law School; I’ve spent a good part of the last two years at Harvard, I’m there right now, and know something about it. He then went on to Chicago, where he taught law at the University of Chicago; I was a visiting professor at the University of Chicago in 1990 and 1991. So I know something about the way in the Middle East is presented and discussed on Morningside Heights, in Cambridge, and in Hyde Park.

The teaching of the Middle East at these universities occupied a considerable chunk of my book Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in America. In the years when young man Obama studied in these institutions, radical professors were thoroughly misrepresenting the realities of the Middle East. And their vantage point, far from being the American interest, was the liberation struggles of oppressed peoples, first and foremost the Palestinians.

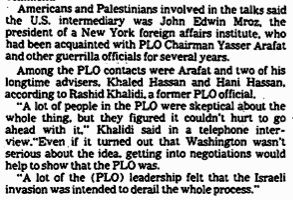

When Obama was at Columbia, at the time of the 1982 war in Lebanon, Columbia professor Edward Said was beating the drums against Israel—he’d just finished and published his book The Question of Palestine, which set the parameters within academe for what one could and couldn’t say about the Palestinians and Israel. Obama came to Harvard not long after a radical insurgency deposed the director of that university’s Middle East Center, a former Israeli, for having received money from the CIA for a conference and book. And when Obama reached Chicago, it was just after I had left, and he would have found a campus where directorship of the Middle East Center had been entrusted to a Palestinian advocate—one who, at the time, was simultaneously advising the PLO delegation to peace talks. I refer here to Professor Rashid Khalidi.

Now it’s extremely difficult to know what sort of primer on the Middle East Obama might have received in the course of his formal education. His Columbia years are a blank. The university hasn’t released a transcript of his courses, and very few classmates have any recollection of him. It’s been rumored that he did some coursework with Edward Said, but I haven’t seen that substantiated anywhere, and his senior thesis dealt with the Soviet Union. (Obama claims to have lost it.) At Harvard, where he studied law, there’s no evidence he had any contact with the Middle East professoriat.

But the University of Chicago is another story. His stay there, as a lecturer and senior lecturer, coincided with the meteoric rise of Rashid Khalidi. I myself came to know Khalidi in the mid-1980s when he was at Columbia. Indeed, it was at a 1986 Columbia conference on Arab nationalism, to which he’d invited me, that he introduced me to Edward Said. (But that’s another story.) In 1990 and 1991, I spent each winter quarter at the Middle East Center of the University of Chicago, to which Khalidi had transferred himself, and where in my second year he was already director.

This period also coincided with the aftermath of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, and America’s first Gulf war. The Middle East Center at that time became a cauldron of antiwar agitation, in which Khalidi took the lead role. I well remember one of several lengthy conversations with him, in which he argued that the American operation to remove Saddam Hussein from Kuwait was a colonial war—his phrase. At that time, he became a predictable echo chamber for Saddam’s propaganda line: Saddam, it will be recalled, claimed to be acting on behalf of the Palestinian cause, and Yasir Arafat went to Baghdad to embrace him. Khalidi never went that far, but he did argue the case for “linkage”—that is, that before the world should presume to ask Saddam to end his occupation of Kuwait, it should pressure Israel to end its occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. Absent that, he thought the United States and the West had no greater moral authority than Saddam.

It’s here that Obama appeared in 1991, and for the first time we can link him to the Edward Said-Rashid Khalidi nexus. It was at the University of Chicago that Khalidi set out to create something like an Edward Said school of Middle Eastern studies. Not only did he encourage students pursuing work validating the theories of Said. In 1994, he arranged for Said to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Chicago. This was the hot place to be for the trendy postcolonialist, blame-America, trash-Israel kind of pseudo-scholarship that first infected Middle Eastern studies in the 1980s. It was at the University of Chicago that it became the most firmly established, and it was there in the early 1990s that Obama befriended Khalidi.

Now I won’t bore you with the details of their relationship. That’s because we don’t have a lot of details. They’ve been obscured or suppressed—by the Obama campaign, and by Khalidi himself, who’s virtually disappeared from the public eye since his name was mentioned in connection with Obama. But from the details we do have, it would appear that Obama received his first primer on the Middle East from Rashid Khalidi.

The clearest evidence for this may be found in a videotape of a farewell dinner for Khalidi in 2003—it was at this time that Khalidi accepted an invitation to return to Columbia University as the Edward Said Professor of Arab Studies. Obama attended that dinner, and testified to the impact of his decade-long friendship with Khalidi. Pointing out that he and his wife Michelle had had many dinners and conversations with Khalidi and his wife Mona, Obama said these talks had been “consistent reminders to me of my own blind spots and my own biases… It’s for that reason that I’m hoping that, for many years to come, we continue that conversation—a conversation that is necessary not just around Mona and Rashid’s dinner table,” but around “this entire world.” This is at least how the event was reported last fall by the Los Angeles Times. The newspaper has declined to release the videotape, which it has in its possession.

This was, by the way, not the only dinner table conversation that Obama conducted on the Middle East in Chicago. There’s also a photograph of Obama and his wife Michelle, seated at a dinner with Edward Said and his wife Mariam. One presumes, of course, that this encounter was also arranged by Khalidi—who, in addition, organized a fundraiser for Obama’s unsuccessful 2000 congressional race.

I suspect there would also have been a very strong resonance between the personalities of Obama and Khalidi, both of whom might be described as marginal men welcomed at the center not despite race or ethnicity, but by virtue of them. And there’s one particularly striking parallel worth noting. Obama, you will recall, was born to a nominally Muslim father, a Kenyan bureaucat, and an American Christian mother, leaving some confusion as to the religious tradition in which he was raised. Exactly the same applies to Khalidi. His father, a nominally Muslim Palestinian bureaucrat working for the United Nations, married his mother, a Lebanese Christian, in a Unitarian Church in Brooklyn, where Khalidi would later attend Sunday school. It isn’t clear to me even today whether Khalidi regards himself as a Muslim or a Christian. Of course, for such people caught between old traditions, radical Third World sympathies often serve as ecumenical substitutes for any one fixed religion.

Now it’s interesting that on one occasion, Obama claimed to have received a very early primer on the Middle East—from a Jewish American camp counselor he encountered in the sixth grade. In an interview with Jeffrey Goldberg, Obama said: “During the course of this two-week camp he shared with me the idea of returning to a homeland and what that meant for people who had suffered from the Holocaust, and he talked about the idea of preserving a culture when a people had been uprooted with the view of eventually returning home. There was something so powerful and compelling for me, maybe because I was a kid who never entirely felt like he was rooted.” And in the continuation of that interview, Obama said: “I think the idea of Israel and the reality of Israel is one that I find important to me personally. Because it speaks to my history of being uprooted, it speaks to the African-American story of exodus.”

This is interesting, because someone like Khalidi would have spoken even more directly to Obama’s history of being uprooted—and so would Edward Said, whose memoir is entitled Out of Place. It seems far more likely that the mature Obama’s decade-long friendship with Khalidi would have superseded the effects of a two-week childhood encounter at a summer camp with someone whose identity is completely unknown, and whose existence is unverified.

I submit that the “conversation” with Khalidi was very much Obama’s primer on the Middle East. We can only speculate as to its precise composition. Perhaps some clues may be found in the book that Khalidi was then preparing, and which eventually appeared under the title Resurrecting Empire. The book is a full-throttle indictment of U.S. policy in the Middle East, American interventionism, the invasion of Iraq, U.S. support for Israel—all the usual tropes so prevalent in Middle Eastern studies, post-Edward Said. This primer would essentially have consisted of two core messages: first, that the use of American force has always been counter-productive in the Middle East, as well as immoral; and second, that many if not all of the problems of the Middle East hinge on the Palestine question, which America has failed to resolve because of its subservience to Israel. (I remind you, parenthetically, that this is similar to the critique of the Israel lobby made by University of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer and Harvard professor Stephen Walt. That’s what happens when you mix Hyde Park with Cambridge.)

Now it would be risky to argue that Obama became some sort of disciple or acolyte of the Edward Said-Rashid Khalidi school. In the course of Obama’s daily duties as a South Chicago politician, he wouldn’t have been called upon to say much about the Middle East or Israel. And it seems logical to assume that as his ambition grew, and began to assume national proportions, he began to appreciate how limiting a left-wing, third worldist, pro-Palestinian posture might be. Obama is nothing if not a quick study, and in a city like Chicago and a state like Illinois, he would have very quickly appreciated the value of support by pro-Israel Jews. Obama didn’t pay his first visit to the Middle East—to Israel—until 2006, by which time he’d completely absorbed the pro-Israel refrain. In Israel, he was treated to the customary helicopter flyover of the West Bank, and said all the right things about Israel’s security needs and the value of the Israeli-American relationship.

And yet. It’s telling, first of all, that Obama has been careful not to distance himself from his first mentor in matters Middle Eastern. Pressed about his friendship with Khalidi, he’s sought to leave the impression that this wasn’t a deep connection. He knows Khalidi, he admits—their children had attended the same privileged Lab School at the University of Chicago. And the two of them had had what Obama calls “conversations.” He has described Khalidi as “a respected scholar,” while emphasizing that Khalidi isn’t an adviser to his campaign.

This suggests to me that the Khalidi connection, while potentially embarrassing to Obama, is still far too significant for him to disavow. And to do so would alienate a considerable body of left-wing opinion, which holds Khalidi to be a personification of Palestine. It’s in Obama’s interest for it to be thought that he intends to continue that “conversation” begun in Hyde Park. And Khalidi, unlike Reverend Wright, has been exceedingly careful not to embarrass his former protege with untoward statements to the media. Before Khalidi went completely silent, he was quoted as saying he supported Obama because “he is the only candidate who has expressed sympathy for the Palestinian cause,” and he lauded Obama for supporting talks with Iran. As Khalidi put it: “If the U.S. can talk with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, there is no reason it can’t talk with the Iranians.”

And that brings me to what I believe are the residual influences of this early primer on the Middle East upon the likely Obama administration. The first concerns the use of force. Any reader of Khalidi’s book, Resurrecting Empire, will inevitably conclude that there is no cause that could ever justify an American use of force in the Middle East. It is everywhere and always counterproductive. The policy advocated by Khalidi toward Middle Eastern radicalism might best be described as supine appeasement. It is America’s use of strong armed force—and the parallel violence of Israel—which have provoked the counter-violence of the extremists. If America were to give up its bullying ways, and address the “grievances” of Arabs and Muslims, the latter would regain their respect for America. There are no pathologies in the Middle East that haven’t been caused by imperialism, and no pathologies that can’t be cured by displays of American humility and penitence.

Now Obama is of course exceedingly careful lest he be regarded by the American public as wholly averse to the use of force. No one who aspires to the title of commander in chief can afford such a public perception. But the logic of appeasement has been cleverly repackaged and renamed. The new moniker is “engagement”—a word that evokes that pragmatic American assumption that “there’s no harm in talking.” The core of Obama’s Middle East policy is a promise to engage, engage, and engage again. He has already made this explicit in the case of Iran—a policy praised, as we’ve seen, by Khalidi, and one that’s now defended and rationalized by all Obama’s many eager advisors, including people who in the past didn’t necessarily think it was a good idea.

Obama has drawn the line, at least for now, between Iran and the many terrorist groups it supports. The United States should engage Iran, but not the Palestinian Hamas—and the Obama campaign went so far as to fire one adviser, Robert Malley, who not only advocated “engagement” with Hamas, but actually seems to have practiced it. But the logic for engaging Iran is really no different than the logic for engaging Hamas, and if you know the right Palestinians, there’s no great difficulty in establishing a discrete back channel.

The other major takeaway from Obama’s early primer is the centrality of the Palestine question to the Middle East. Back in May, Obama was asked whether he thought Israel was, “a drag on America’s reputation overseas.” Obama replied: “No, no, no. But what I think is that this constant wound, that this constant sore, does infect all of our foreign policy.” This followed, by only five days, an article in The Nation by Khalidi, where the Palestinian professor wrote: “The ‘Palestine Question’ has been with us for sixty years. During this time it has become a running sore, its solution appearing ever more distant.” The wording may or may not be a coincidence. But the belief in “linkage”—the centrality of the “Palestine Question” to just about everything—is one that seems to have been perfectly assimilated by Obama.

He might have heard it first from Khalidi; it would have been reinforced by advice given to him by Zbigniew Brzezinski; and it was most recently reinforced to Obama by Jordan’s King Abdullah, during Obama’s summer Middle East junket. Back from his trip, Obama explained the lesson he’d learnt from the King:

We’ve got to have an overarching strategy recognizing that all these issues are connected. If we can solve the Israeli-Palestinian process, then that will make it easier for Arab states and the Gulf states to support us when it comes to issues like Iraq and Afghanistan. It will also weaken Iran, which has been using Hamas and Hezbollah as a way to stir up mischief in the region. If we’ve gotten an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal, maybe at the same time peeling Syria out of the Iranian orbit, that makes it easier to isolate Iran so that they have a tougher time developing a nuclear weapon.

This is, of course, a reworking of the old Arabist trope, that America can’t achieve anything in the Middle East unless and until it solves the “Palestine Question.” And the direct implication is that an intransigent Israel is screwing things up for the United States from Kabul to Tehran to Baghdad. Elsewhere I’ve written about the mythical quality of this belief in an Archimedean point, from which one can leverage change throughout the Middle East. It just doesn’t exist. The fact that Obama thinks it does, despite being told the contrary by some of his more realistic advisors, suggests that at least some of the ideas he ingested at Khalidi’s dinner table have stuck to his ribs.

Obama has surrounded himself with various advisers—latecomers, not within his inner circle—who hold different views. They include, most notably, Dennis Ross and Daniel Kurtzer. Obviously, they don’t belong to the blame America-school of Rashid Khalidi. But Obama staked out his Iran position before they came on board, and they seem to have moved in his direction rather than vice versa—that is, they now justify unconditional talks with Iran. And it goes without saying that for such advisers—who are, themselves, professional peace processors—an administration which will endlessly preoccupy itself with Israelis and Palestinians is a gift from above. They are not likely to disabuse their boss of the notion of “linkage,” even if they don’t entirely subscribe to it. It matters not that the last administration they served preoccupied itself in a similar manner, producing a blowup from which the Middle East has yet to entirely recover.

The ultimate question isn’t whether Obama will unlearn what he learned at Columbia, Harvard, and Chicago. Should he actually initiate unconditional talks with Iran, it will dawn on him at some point that this was a mistake—that it legitimated the Iranian regime without receiving any concession in return, especially regarding Iranian conduct in Iraq and Lebanon; that it undermined the already fragile coalition of Arab states build so painstakingly by the Bush administration to contain Iran; and that it gave Iran an opportunity to continue its nuclear program under the cover of negotiations, perhaps buying enough time to bring it to completion.

When Obama realizes this, he will face the very same narrow choice of options he wishes now to avoid: that is, either acquiescence in a nuclear Iran, or a military strike. Of course, when “engagement” fails, there will still be a sizable body of Muslim, European, and American opinion which will hold the United States to blame, for not going the extra mile. And even though Obama will have gone the extra mile, he’ll be criticized for not going yet another. This is the relentless logic of appeasement. But when “engagement” finally fails, Iran’s programs will be still further advanced, making the military option even less appealing than it is today. So “engagement” is not so much a third alternative between a nuclear Iran and a military strike, as it is a likely prelude to American acquiescence in a nuclear Iran. This would constitute one of the greatest failures of American foreign policy ever.

Likewise, the attempt to accelerate Israeli-Palestinian negotiations will simply mean they’ll fail even more resoundingly than they’re failing now. The present process has gone nowhere, but because expectations are so low, the impact of their slow-motion failure has been minimal. Indeed, at the present moment, Israel and the Palestinian Authority have actually made considerable progress on security arrangements, which allows a modicum of normal life for Israelis and Palestinians alike. The West Bank is even drawing foreign investment, the economy is improving, and property values are rising. A flashy, high profile peace initiative, captained by the old recycled peace processors, will put all of this at risk, by raising expectations that can’t possibly be met. For such a process to move anywhere, it will be necessary to somehow put the Palestinian Humpty Dumpty together again—an effort destined to undermine the authority of Mahmoud Abbas. It will also be necessary to push Palestinian leaders toward concessions they can’t possibly make. The last time this happened, in 2000, in very similar circumstances, the Palestinians blew up and began to blow Israelis up.

One can only hope that Obama realizes sooner rather than later that he too will not be able to draw the sword from the stone and bring about an Israeli-Palestinian peace in our time. But lots of time and energy will be wasted in this learning process, it will put tremendous strain on the triangular relationship among the United States, Israel, and America’s Arab allies, and it will distract everyone from what has to be done to address the other pressing problems in the Middle East, all of which will be neglected on the erroneous assumption that America can’t do anything productive until it creates some sort of Palestine.

Now Obama strikes me as a pragmatic politician, who’ll probably learn lessons even faster than his advisers, locked as they are in postures they assumed way back in the Clinton years. By the time the four years of a first-term are over, I would be surprised if he hasn’t unlearned all lessons taught to him by his Palestinian mentor, and escaped even their residual influences. But in the course of doing so, the security and stability of the Middle East could be put at considerable risk. It was Albert Einstein who described insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting different results. So the United States will try to talk the radicals out of being radical, and once again it will fail. And the United States will try to talk Israelis and Palestinians into a final peace for all times which neither of them wants as much as America wants it, and once again it will fail.

Which is all the more reason, now, for thinking people to work hard on alternatives that will become relevant in another two years, when reality sinks in and illusions are shed. From the very first day of the next administration, it will be necessary to point out the risks that attend to “engagement” and “linkage.” It’s too late for myself and others to provide the next president with his primer—someone else already did that. But when that president shows himself in need of some remedial education, we have to be there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.