Werner Ende (1937-2024), who passed away on August 6, was described in these words in an obituary by a former student, published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung:

His students now work in intelligence services, media outlets, and universities: Werner Ende, who profoundly influenced modern Islamic studies in Germany, has passed away.

In Germany, research into contemporary issues of the Middle East doesn’t have a long tradition. Philologists and cultural scholars were often too afraid of being co-opted for political purposes. For a long time, they preferred to focus on ancient manuscripts and retreat into the academic ivory tower. When the world became interested in the Islamic world after the Iranian Revolution of 1979, there was little from the Orientalist departments that could explain what was happening in neighboring regions. This has changed; today, Islamic studies as a branch of Orientalism is no longer seen as an obscure or irrelevant field.

This shift is thanks in part to Werner Ende, a pioneer in modern Islamic studies.

It was this role that drew me to Ende, the German scholar with whom I had the closest relationship. By the time I met him in 1986, he had moved beyond his early work on Arab nationalist historiography to establish himself as a leading expert on Salafi Islam and Shi‘ism in its Arab contexts. Sunni-Shi‘ite polemics became his special field of interest, and he approached them from both sides with the factual and philological precision characteristic of the German scholarly tradition.

Like my mentor, Bernard Lewis, Ende insisted that the politics of Islamic movements could not be understood without a profound grasp of early Islamic history. Only Ende could explain, with absolute authority and clarity, how today’s Saudi-Iranian dispute over a cemetery in Medina encapsulated centuries of Wahhabi-Shi‘ite rivalry. His study of the Shi‘ites of modern Medina is a typical gem, all the more remarkable since, as he admitted, he had “not been able—and most probably never will be—to do research on the spot.” These deep dives into difficult texts revealed him as a virtuoso researcher, whose resourcefulness was truly astonishing.

In 1986, I went to Freiburg im Breisgau, where he held the chair in Islamic studies, to spend a month under his tutelage. Ende became my guide to many things that summer: the revival of the German Orientalist tradition after the devastation of the Second World War, Shi‘ism in Lebanon (where he had spent several years before that country’s civil war), and Wahhabi ideology. His tutorials over Kaiserstuhl wine atop Freiburg’s Schlossberg were unforgettable.

We stayed in touch; I last saw him over breakfast in Berlin in 2016. He had retired by then and moved to the reunited capital. (In his youth, he had lived in East Berlin near the Wall and escaped to the West in pursuit of freedom. Life under communism made him wary of all forms of indoctrination.) I last corresponded with him in 2023, when he told me he had fallen seriously ill and had returned to the care of family in Freiburg, where he passed away.

Ende was largely unknown outside the German-speaking world. He published some articles in English, but not a book (apart from two co-edited volumes), and he didn’t attend conferences in America. However, he exhibited a keen and mischievous curiosity about the battles over Middle Eastern studies across the Atlantic. While he kept his distance from the Arab-Israeli conflict, he did not distance himself from Israel or Israeli scholars. His most accessible summary of Sunni polemics against Iran’s revolution appeared (in English) in an Israeli conference volume—an article that is more relevant than ever today.

More important than international renown, he was a devoted mentor to many students, who attest to his lasting influence on their work and careers. They compiled a fine collected volume in celebration of his 65th birthday, the title of which takes on a different meaning today. It played on his name: Islamstudien ohne Ende (‘Islamic studies without end’). Now Islamic studies in Germany are without Ende, but hopefully not without his standards of rigorous scholarship.

In 1988, he reviewed my first book, Islam Assembled, published in 1986. I reproduce it at this link (translated from German) not because it flattered me. My book was a revised doctoral dissertation, and from my present perspective, I’m embarrassed by its flaws. It’s also true that by the time Ende wrote his review, we were already on friendly terms. But it reflected his generosity of spirit, and his emphases suggest why we connected. Rereading it now, almost forty years later, it strikes me as a model of how a senior scholar should review the work of a promising junior one. There is always fault to be found, but it should be weighed against the value of unqualified praise for someone launching a career. I shall always be grateful for his kindness.

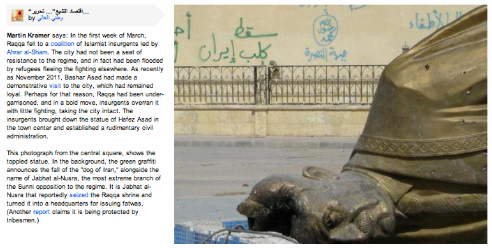

Header image: Baqi‘ cemetery in Medina. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

You must be logged in to post a comment.