In 2015, I gave a lecture on the deeper historical background to the civil war in Syria, and I published it in my 2016 book The War on Error. Under present circumstances, it seems as relevant as ever, and I wouldn’t change a word.

When the revolution (or uprising, or insurgency) started in Syria in 2011, many people saw it as the obvious continuation of the so-called Arab Spring. There had been revolutions in Tunisia, then Egypt and Libya—countries with Mediterranean shorelines. When conflict broke out in Syria, analysts initially read it as an extension of the same process.

In retrospect, it was not. The countries of North Africa are fairly homogeneous and overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim. There are regional and tribal differences in Libya, and Egypt has an important Coptic Christian minority. But revolutions in these countries did not involve the transfer of power from one religious or sectarian or ethnic group to another.

In Syria, political transformation threatened to do precisely that. And so what evolved in Syria wasn’t an extension of the “Arab Spring,” but a continuation of another series of conflicts, far more devastating in their effects. Going back from the present moment, chronologically, its predecessors included the post-2003 Iraqi civil war, the Kurdish insurgency in Turkey, the Lebanese civil war from 1975 through 1989, and, still more remotely, the Armenian genocide of 1915. These might conveniently be called the wars of the Fertile Crescent.

What is the Fertile Crescent?

What the Arabs somewhat laboriously call “Iraq and Sham” or “Iraq and the Levant” (from which derive ISIS and ISIL) has a perfectly serviceable English name. It was invented by James Henry Breasted, an American Egyptologist at the University of Chicago, and popularized in his 1916 book Ancient Times. Breasted defined the Fertile Crescent as the expanse of territory set between the desert to the south and the mountains to the north—a place constantly under pressure from invaders, precisely because it is sustaining of life (Breasted called it “the cultivable fringe of the desert”). He marked it as a zone of “age-long struggle … which is still going on.”1

“Fertile Crescent” gained popularity in the West because it seemed fertile in another way, as the site of the earliest biblical narratives and the birthplace of monotheism. It was the presumed locale of the Garden of Eden, which generations of early cartographers sought to place on a map.2 It was the site of the Tower of Babel, which purported to explain the emergence and diffusion of different languages. It was the stage for the wanderings of the patriarch Abraham, who crossed it from east to west—a migration in the course of which he came into communion with the one God. The Bible, before it linked the Holy Land to Egypt, linked it to Mesopotamia. And while the peoples of the Fertile Crescent may have been many, and of many languages, they were the first to imagine God as one.

The Fertile Crescent thus came to signify diversity amidst unity: a multitude of peoples believing in the existence of one God. This was in contrast to Greece and Egypt, which were cases of single peoples of one ethnic origin and language believing in many gods. It was in the Fertile Crescent that Islam would be tested as a unifying force for diverse populations. Only after passing that test did it expand across the globe. The Fertile Crescent itself then would be folded into the great Islamic empires. In the last of them, the Ottoman, it sometimes flourished and more often languished as a single, borderless expanse.

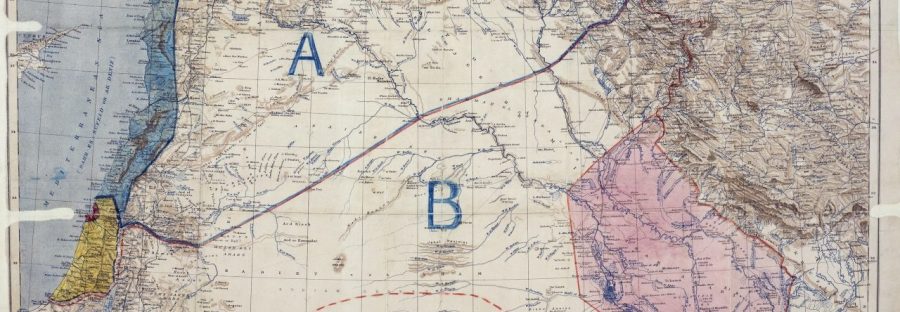

Sykes-Picot

But in 1916, the same year that Breasted popularized the phrase Fertile Crescent, Britain and France concluded the Sykes-Picot agreement for the partition of the Ottoman Empire, dividing this zone into states and drawing straight borders through the desert. Within those borders, Britain and France imposed one faction over all others in political orders that depended to some degree or another on coercion. Power in Iraq and Syria coalesced around minorities. In Iraq, a Sunni minority was imposed over a Shi‘ite majority; in Syria, a Shi‘ite-like minority, the Alawis, over a Sunni majority. (The Kurds, minorities in both countries, were at the bottom of the heap.)

In Mesopotamia, Britain imported a Sunni monarchy from Arabia and bound it to the indigenous Sunnis of Baghdad and its surroundings, giving them dominion over a vast territory unified under the name of Iraq. The French initially tried a very different approach in Syria. Whereas the British sought to unify, the French originally intended to divide: for a period in the 1920s and 1930s, what would become Syria was in fact divided into an Alawite state, a Druze state, the states of Aleppo and Damascus, and Lebanon. In 1937, the French acceded to the demands of Syrian nationalists, and also unified Syria (excluding Lebanon). But at the same time, the French worked to empower minorities, above all the Alawis, by recruiting them into the military, in order to keep Arab nationalism in check. After independence, the Alawis parlayed that advantage into their own dominion.

While the rulers of Syria and Iraq stood, from a sectarian point of view, on opposite ends of the spectrum, they were both cases of post-colonial minority-domination in states engineered from the outside. Still, there was a difference. Syria’s ruling minority was much more of a minority. The Alawis in Syria are probably no more than twelve percent of the population whereas the Sunnis in Iraq are probably about twice that percentage. And while the ruling Sunni minority in Iraq had an integral connection with the wider Sunni majority in the region, the ruling Alawis in Syria had no such backstop, and ended up relying on distant Iran.

Perhaps Breasted would have warned us that this order couldn’t last. That it lasted as long as it did was the result of ruling minorities modernizing their repressive machinery in ways the ancients could never have imagined. But this machinery was discredited and dismantled by the United States in Iraq, and it has broken down from within in Syria. Power is now shifting from one religious or sectarian group to one which happens to be larger or more powerful or more connected to sources of outside support. Or it is fragmenting altogether.

From Strength to Weakness

There is much irony in the contraction of Iraq and Syria. Both states, at their twentieth-century high watermarks, were strong enough to project their power beyond their borders, and they even tried to redraw them. Iraqi nationalists believed that Iraq should have been awarded still wider borders, especially along the Persian Gulf littoral. Syrian nationalists likewise claimed that “greater” Syria should have been incorporated within Syria’s borders. The 1919 General Syrian Congress passed this resolution: “We ask that there should be no separation of the southern part of Syria, known as Palestine, nor of the littoral Western zone, which includes Lebanon, from the Syrian country. We desire that the unity of the country should be guaranteed against partition under whatever circumstances.”3

But it wasn’t to be. A separate Lebanon and Palestine came into existence. For this reason, Syria refused to reconcile itself to its own borders. Indeed, for three years, from 1958 to 1961, Syrians readily agreed to dismantle their own independent state, and incorporate Syria into a union with Egypt called the United Arab Republic.

Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, when he thought he had the opportunity, attempted to redraw Iraq’s borders by force, through his invasion of Iran and his occupation and annexation of Kuwait. Syrian president Hafez Assad likewise occupied Lebanon and gave safe haven to the Kurdish PKK, which was headquartered in Damascus. Iraq and Syria seemed to have become powers in their own right. In the case of Syria, in particular, American secretaries of state and even presidents came to Damascus as supplicants, hoping to win its ruler over to their geopolitical concepts of regional order.

Now all that has been reversed. Not only is Syria no longer capable of projecting its power beyond its borders; others are meddling inside Syria, to advance their own agendas, in alliance with the various domestic factions, while Syrian refugees flee the country in the millions. Syria’s elites once regarded the state’s external borders as inadequate to Syria’s great historical role, but Syria is now incapable of preserving unity even in its “truncated” borders. Syrians were educated to believe that the state of Syria was the nucleus of a greater Syria, itself the nucleus of a greater Arab unity. But in practice, Syria itself could not resist imploding into a de facto partition, driven by deep internal divisions.

Now it is not Syria’s power, but Syria’s weakness, that threatens the region. Albert Hourani, the historian of the Middle East, once wrote this: “Even were there no Syrian people, a Syrian problem would still exist.”4 That is exactly where the Middle East is now stuck. There is no Syrian people, but there is still a Syrian problem, and it will continue to dominate the region and worry the world, perhaps for years to come.

Since this disorder has no name—certainly none as succinct as “Sykes-Picot”—I propose to call it, for now, the Breasted Fertile Crescent. This would be a Fertile Crescent made up of shifting principalities, subject to occasional intervention by surrounding powers, characterized by variety and diversity, essentially without fixed borders—a place where Shi‘ites struggle against Sunnis, Arabs against Kurds, the desert against the sown. The Breasted (dis)order will persist, until some great outside power or group of regional powers proves willing to expend the energy needed to restructure the Fertile Crescent in accord with their interests—something the Ottomans did for four hundred years, Europe did for fifty years, and America has not yet attempted at all.

Notes

- James Henry Breasted, Ancient Times: A History of the Early World (Boston, MA: Ginn, 1916), 100–1.

- See Alessandro Scafi, Mapping Paradise: A History of Heaven on Earth (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

- J. C. Hurewitz, The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics: A Documentary Record, vol. 2: British-French Supremacy, 1914–1945 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), 181.

- A.H. Hourani, Syria and Lebanon: A Political Essay (London: Oxford University Press, 1946), 6.

You must be logged in to post a comment.