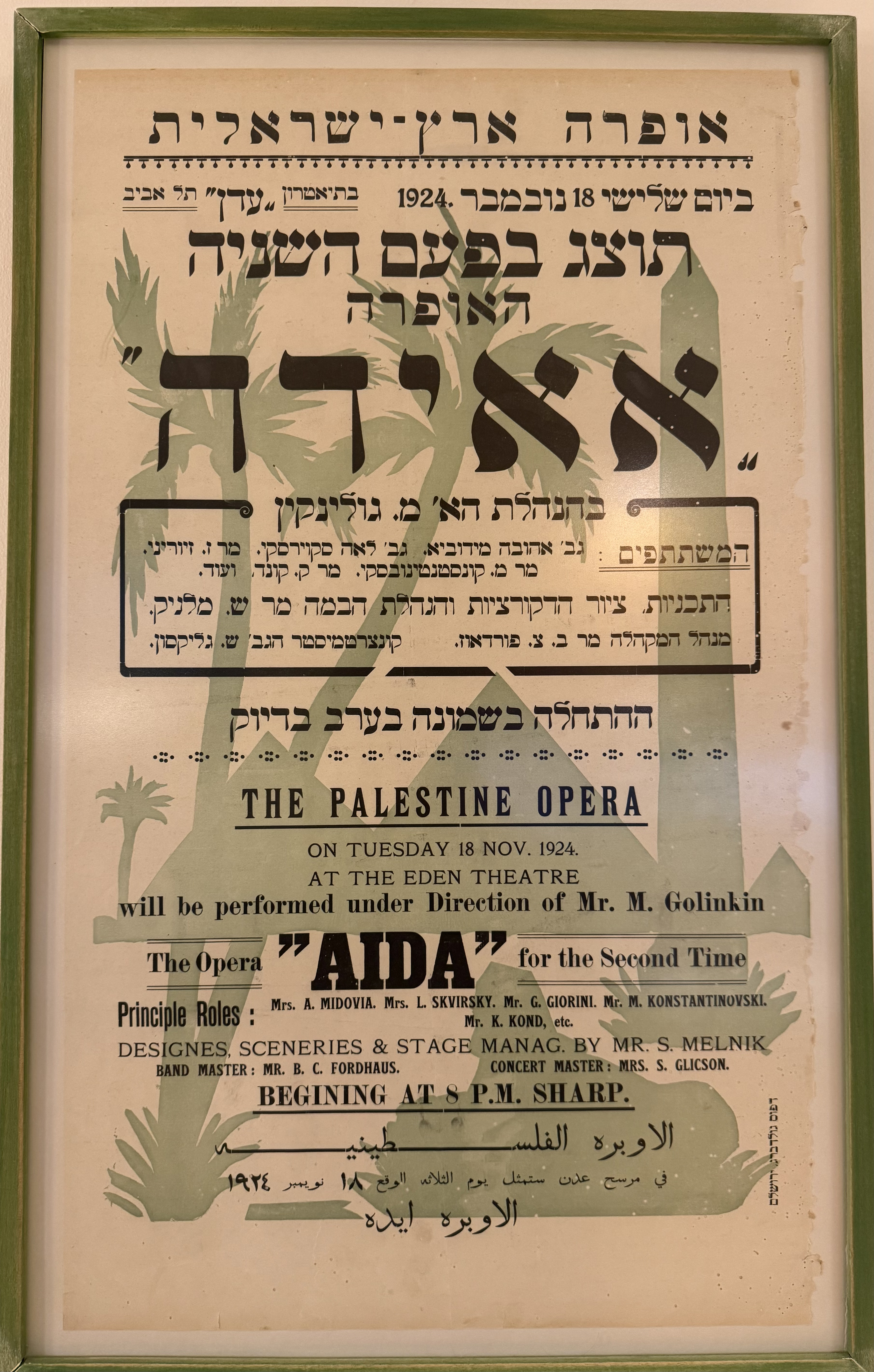

Some years ago, I purchased a delightful 1924 poster at auction, advertising a performance of Verdi’s opera Aida by the Eretz-Israel (Palestine) Opera in Tel Aviv. The date of the performance? Exactly a century ago: November 18, 1924. The poster reads: “The Opera ‘Aida’ will be performed for the second time under the Direction of Mr. M. Golinkin at the Eden Theatre… beginning (spelled as ‘begining’) at 8 p.m. sharp.” The poster’s three languages are arranged in blocks, with Hebrew at the top, English in the middle, and Arabic at the bottom, likely reflecting the expected audience interest in the production.

I was drawn as much to the aesthetics of the poster as to its content. The Giza Pyramids, the Sphinx, an obelisk, and green palm trees dominate the background, evoking the exotic landscape of Egypt. The poster features a limited palette of pastel green and black on a white background, now yellowed with age. The pastel green complements the palm tree imagery. A riot of fonts and typographical elements in all three languages—along with misspellings and unusual spellings—further enhances its charm.

Mordechai Golinkin was a trailblazer for opera in the Yishuv. Born in the Russian Empire, he displayed exceptional musical talent from an early age and earned widespread acclaim as a conductor. Inspired by the Balfour Declaration, Golinkin founded a Jewish choir that toured Russia to raise funds for establishing an opera in Palestine. In 1923, he arrived in Tel Aviv and founded the Eretz-Israel (Palestine) Opera. Despite precarious finances and makeshift venues, he staged eighteen Hebrew-translated productions during the Opera’s four years under his leadership. When the funds were exhausted, opera largely disappeared from Mandatory Palestine. However, in the 1940s, Golinkin encouraged the revival of the genre by successors, and at the age of 73, he conducted the inaugural performance of the Israel National Opera in 1948.

The 1924 performance advertised on my poster was held at the Eden Theater, then a silent movie house in Tel Aviv’s Neve Tzedek neighborhood. Opened in 1914, the original (“winter”) theater was a concrete marvel of its time, seating 800 people under one roof. (The long-abandoned Eden is now slated to become a luxury hotel.) The poster’s warning that the performance would begin at 8 p.m. “sharp” was no mere formality. Golinkin later lamented that Tel Aviv’s residents were “unused to punctual theater attendance,” arriving late and having to stand in the corridor behind the doors for the entire first act of the Opera’s premiere performance.

I attempted to find information about the performance of Aida at the Eden Theater but couldn’t locate a review. However, I did come across an amusing piece in the Ha’aretz daily, published the morning after the November 18 performance, offering readers tips on how to enjoy the next performance for free. The advice appeared in an “About Town” column, credited to a pseudonym I couldn’t decipher. My translation follows.

Aida on the Cheap

Anyone who cannot afford three liras for a room, a penny for an egg, pennies for a glass of milk, a few coins for a loaf of bread that doesn’t quite meet weight standards, a lira for a minor luxury, or earns 25 mils a day in torn trousers, or generally anyone who either wishes but cannot or can but does not wish to buy a ticket for the opera Aida and listen to Radamès, is invited to come tomorrow to the Eden (but not all the way in) and secure an appropriate spot around its perimeter. The grounds are expansive and welcoming, the walls of the Eden are thin, its upper windows are wide open, and the voices of the singers are powerful enough to reach every heart. The visitor will assuredly hear the opera in all its precision. And if the cries of the boy hawking the daily Do’ar Hayom don’t shake the foundations of the temple while the priests are performing their rituals, the ballet is dancing, and the trumpets are blaring, it will still be possible—even for an untrained ear—to distinguish between the cracking of sunflower seeds and the shelling of pistachios in some discreet corner of the Eden, or hear the sound of the libretto’s pages being turned by the audience, and even the beating hearts of the new singers making their debut in Tel Aviv for the first time—not to mention clearly hearing, very clearly indeed, the tapping rhythm of Golinkin’s right foot or his soft whisper, like a pssst, directed into an ear:

“Play forte, my friends. Softly now, thieves.” In moments of anger: “Pianissimo, you devils!”

Those who wish may also bring ladders (as is customary), lean them against the walls, and climb higher and higher to the small windows, enhancing the experience by adding sight to sound.

The opera management may rest assured that this reverent audience will examine every detail with a precision finer than a hair’s breadth, interpreting everything beyond the strict letter of the law. The gathering will arrive at the Eden an hour before eight and remain outside until midnight, even though the press of people will be great, the winds cold, and the rains dripping—and, of course, no one will have a raincoat.

Source: Ha’aretz, November 19, 1924. Header image: Original Eden Theater in 1914.

You must be logged in to post a comment.