The Wall Street Journal ran a symposium over the weekend about world reactions to Obama’s Syria turnaround. I wrote the contribution on Israel. Many aspects of the “turnaround,” especially the enhanced role of Russia in the Middle East, impact Israel. But I focused instead on Obama’s earlier “turnaround”: his decision to seek authorization for military action from Congress. Excerpt:

What Israelis found alarming was the way Mr. Obama shifted the burden of decision. Every one of Mr. Obama’s Syrian maneuvers was viewed as a dry run for his conduct in a likely future crisis over Iran’s nuclear drive. That’s where the stakes are highest for Israel, and that’s where Israelis sometimes question Obama’s resolve.

Israelis always imagined they would go to Mr. Obama with a crucial piece of highly sensitive intelligence on Iranian progress, and he would make good on his promise to block Iran with a swift presidential decision. So Mr. Obama’s punt to Congress over what John Kerry called an “unbelievably small” strike left Israelis rubbing their eyes. If this is now standard operating procedure in Washington, can Israel afford to wait if action against Iran becomes urgent?

Israel’s standing in Congress and U.S. public opinion is high, but the Syrian episode has shown how dead-set both are against U.S. military action in the Middle East. Israel won’t have videos of dying children to sway opinion, and it won’t be able to share its intelligence outside the Oval Office. Bottom line: The chance that Israel may need to act first against Iran has gone up.

Why was Obama’s recourse to Congress so alarming? Israel has long favored strong presidential prerogatives. That’s because the crises that have faced Israel rarely ever leave it the time to work the many halls of Congress. Israel discovered the dangers of presidential weakness in May 1967, when Israel went to President Lyndon Johnson to keep a commitment—a “red line” set by a previous administration—and Johnson balked. He insisted he would have to secure congressional support first. That show of presidential paralysis left Israel’s top diplomat shaken, and set the stage for Israel’s decision to launch a preemptive war.

2013 isn’t 1967. But Israel long ago concluded that the only thing as worrisome as a diffident America is a diffident American president—and that a president’s decision to resort to Congress, far from being a constitutional imperative, is a sign of trouble at the top.

“Not worth five cents”

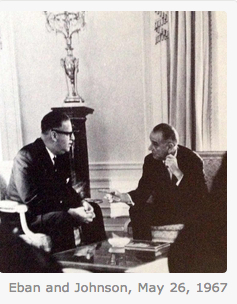

What did Israel want from Lyndon Johnson in May 1967? On May 22, in the midst of rising tensions across the region, Egypt’s president Gamal Abdul Nasser announced the closure of the Straits of Tiran to Israel-bound ships headed for the port of Eilat, effectively blockading it. More than a decade before that, in 1956, Israel had broken a similar Egyptian blockade by invading and occupying the Sinai. Israel withdrew in 1957, partly in return for an American assurance that the United States would be “prepared to exercise the right of free and innocent passage [through the Straits] and to join with others to secure general recognition of this right.” In 1967, when Nasser reimposed Egypt’s blockade, Israel asked the United States to make good on that 1957 commitment, by leading an international flotilla through the Straits to Eilat. Israeli foreign minister Abba Eban flew to Washington and met with Johnson in the Yellow Oval Room on May 26 to make Israel’s case.

Johnson astonished Eban by pleading that he didn’t have sufficient authority to act. The U.S. memorandum of conversation summarized it this way:

President Johnson said he is of no value to Israel if he does not have the support of his Congress, the Cabinet and the people. Going ahead without this support would not be helpful to Israel…

We did not know what our Congress would do. We are fully aware of what three past Presidents have said but this is not worth five cents if the people and the Congress did not support the President…

If he were to take a precipitous decision tonight he could not be effective in helping Israel… The President knew his Congress after 30 years of experience. He said that he would try to get Congressional support; that is what he has been doing over the past days, having called a number of Congressmen. It is going reasonably well…

The President said again the Constitutional processes are basic to actions on matters involving war and peace. We are trying to bring Congress along. He said: “What I can do, I do.”

Abba Eban later gave a more devastating version of the “five-cent” quote: “What a president says and thinks is not worth five cents unless he has the people and Congress behind him. Without the Congress I’m just a six-feet-four Texan. With the Congress I’m president of the United States in the fullest sense.” According to the Israeli record of the meeting, Johnson also acknowledged that he hadn’t made his own progress on the Hill: “I can tell you at this moment I do not have one vote and one dollar for taking action before thrashing this matter out in the UN in a reasonable time.” And Johnson ultimately put the onus on Israel to get Congress on board: “Unless you people move your anatomies up on the Hill and start getting some votes, I will not be able to carry out” American commitments.

Johnson must have understood the impression he was leaving upon Eban. In the Israeli record, there are two remarkable quotes: “I’m not a feeble mouse or a coward and we’re going to try.” And: “How to take Congress with me, I’ve got my own views. I’m not an enemy or a coward. I’m going to plan and pursue vigorously every lead I can.” That Johnson twice had to insist that he wasn’t a coward suggested that he realized just how feckless he must have seemed.

In his two memoirs, Eban recalled his astonishment at this apparent abdication:

I remember being almost stunned by the frequency with which [Johnson] used the rhetoric of impotence. This ostensibly strong leader had become a paralyzed president. The Vietnam trauma had stripped him of his executive powers….

I’ve often ask myself if there was ever a president who spoke in such defeatist terms about his own competence to act…. When it came to a possibility of military action—with a risk as trivial, in relation to U.S. power, as the dispatch of an intimidatory naval force to an international waterway—he had to throw up his hands in defeat…. On a purely logistical level, this would have been one of the least hazardous operations in American history—the inhibitions derived entirely from the domestic political context. The senators consulted by Johnson were hesitant and timorous. They thought that the possibility of Soviet intervention, however unlikely, could not be totally ignored.

The revulsion of Americans from the use of their own armed forces had virtually destroyed his presidential function. I was astonished that he was not too proud to avoid these self-deprecatory statements in the presence of so many of his senior associates. I thought that I could see [Defense] Secretary McNamara and [chairman of the Joint Chiefs] General Wheeler wilt with embarrassment every time that he said how little power of action he had.

The tactical objective, the cancellation of the Eilat blockade, was limited in scope and entirely feasible. It was everything that the Vietnam war was not. Lyndon Johnson’s perceptions were sharp enough to grasp all these implications. What he lacked was “only” the authority to put them to work. Less than three years after the greatest electoral triumph in American presidential history he was like Samson shorn of his previous strength…. With every passing day the obstacles became greater and the will for action diminished. He inhabited the White House, but the presidency was effectively out of his hands.

After the meeting, Johnson wrote a letter to Israeli prime minister Levi Eshkol, reemphasizing the primacy of the Congress: “As you will understand and as I explained to Mr. Eban, it would be unwise as well as most unproductive for me to act without the full consultation and backing of Congress. We are now in the process of urgently consulting the leaders of our Congress and counseling with its membership.” This was actually an improvement on the draft that had been prepared for him, and which included this sentence: “As you will understand, I cannot act at all without full backing of Congress.” (Emphasis added.) That accurately reflected the essence of the message conveyed to Eban, but Johnson was not prepared to admit his total emasculation in writing.

There is a debate among historians as to whether Johnson did or didn’t signal a green light to Israel to act on its own. It finally did on June 5.

“Too big for business as usual”

In light of this history, it’s not hard to see why Israel would view any handoff by a president to the Congress in the midst of a direct challenge to a presidential commitment as a sign of weakness and an indication that Israel had better start planning to act on its own. It’s not that Israel lacks friends on the Hill. But in crises where time is short and intelligence is ambivalent—and such are the crises Israel takes to the White House—Israel needs presidents who are decisive.

In seeking congressional authorization for military action in Syria, President Obama did not negate his own authority: “I believe I have the authority to carry out this military action without specific congressional authorization.” But “in the absence of any direct or imminent threat to our security,” and “because the issues are too big for business as usual,” he went to the Congress, so that “the country” and “our democracy” would be stronger, and U.S. action would be “more effective.”

Views differ differ as to whether the precedent just set will bind Obama (or his successors) in the future. But Israel understandably has no desire to become the test case, should it conclude that immediate action is needed to stop Iran from crossing Israel’s own “red lines.” Iran’s progress might not pose an imminent threat to U.S. security, and a U.S. use of force would definitely be “too big for business as usual.” So if those are now the criteria for taking decisions out of the Oval Office, Israel has reason to be concerned.

And they may well be the criteria. In 2007, then-Senator Obama was asked in an interview specifically about whether the president could bomb suspected nuclear sites in Iran without a congressional authorization. His answer:

Military action is most successful when it is authorized and supported by the Legislative branch. It is always preferable to have the informed consent of Congress prior to any military action.

As for the specific question about bombing suspected nuclear sites, I recently introduced S.J. Res. [Senate Joint Resolution] 23, which states in part that “any offensive military action taken by the United States against Iran must be explicitly authorized by Congress.”

That resolution went nowhere, but it establishes a strong presumption that Obama would insist on securing congressional authorization for the future use of force against Iran. Depending on the timing, that could put Israel in an impossible situation similar to that it faced in May 1967. Perhaps that’s why one of Israel’s most ardent supporters, Harvard Law professor Alan Dershowitz, has urged that Obama ask Congress now to authorize the use of force against Iran. Senator Lindsey Graham has proposed just that, without waiting for Obama: “I’m not asking the president to come to us; we’re putting it on the table, because if we don’t do this soon, this mess in Syria is going to lead to a conflict between Israel and Iran.”

Whether such an authorization-in-advance is feasible is an open question. In the meantime, there’s always the very real prospect that history could do something rare: repeat itself. In 1967, Israel faced a choice between an urgent need to act and waiting for a reluctant Congress to stiffen the spine of a weakened president. Israel acted, and the consequences reverberate to this day. Faced with a similar choice in the future, it is quite likely Israel would do the same.

This post first appeared on the Commentary blog on September 17.

You must be logged in to post a comment.