Martin Kramer delivered these remarks to a closed session of the board of trustees of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. The session was devoted to the Middle East in the 2008 elections, and it was held in Lansdowne, Virginia on October 19, 2007. Chair: Robert Satloff, director of the Institute; co-panelist, Dennis Ross, Institute distinguished fellow. Posted retroactively at Sandbox.

Thanks, Rob. As Rob has pointed out, I’m an adviser to a political campaign—I’m the senior Middle East adviser to the Giuliani campaign. If you’d compiled a list of people at The Washington Institute likely to end up with such an exalted title in any of the campaigns, Dennis Ross would have been at the top, and I’d have been at the bottom. I certainly didn’t seek it, because I didn’t imagine it.

Now I’m in the idea business. I didn’t get the call because of my experience in government—I haven’t got any—or my personal charm or connection to the candidate—I hadn’t met the Mayor. I like to think I was approached because at least some of my ideas resonated in the Giuliani campaign.

Now as an adviser, I simply continue to do what I’ve always done, which is look hard at the Middle East, and speak what I believe to be the truth. I also listen to other advisers, and learn from them. The point I want to emphasize this morning is that I’m not a spokesperson for the campaign—I provide input, not output. If you want output, read the Mayor’s Foreign Affairs article and listen to him speak. Nor have I turned into an instant analyst of American politics. I don’t closely watch the other candidates, Republican or Democrat, and it’s not my job to campaign.

My aim is to make sure that if Mayor Giuliani is elected president a year from now, he’ll have a full panoply of realistic ideas about what’s needed and feasible in the Middle East, to take with him to the White House two months later.

So this morning, I won’t speak for the Mayor, or indulge in campaigning, or parse the positions of the candidates. Instead I’ll talk about what I see as the stakes in this election. I believe my ideas largely conform to the Mayor’s stated positions, and where they do, I’ll mention them, or my understanding of them. By the way, it’s no small matter to keep up with what a candidate says on the road. He’ll be asked a question on Iran or Iraq by a voter in New Hampshire or Iowa, and I won’t know the answer before you do. But I know I’ve made the right choice because I haven’t been unpleasantly surprised. There are advisers to other campaigns who can’t say the same.

So that’s my preamble. Now to substance. It’s obvious that a lot of what’s at stake in this election turns on America’s role in the Middle East. But before we break it down to specific issues, we have to step back and ask a big question. The big question is this: are we really in a war on terror?

That question’s been sharpened for us by Tom Friedman and Norman Podhoretz. Friedman recently published a column in the New York Times under the headline “9/11 is Over.” Podhoretz has published a new book under the title World War IV. These two ideas—”9/11 is Over” and “World War IV”—neatly define the two opposite poles of the debate that’s at the very heart of this election.

In his piece, Friedman wrote this: “I will not vote for any candidate running on 9/11. We don’t need another president of 9/11. We need a president for 9/12. I will only vote for the 9/12 candidate. What does that mean? This: 9/11 has made us stupid.” Why? It’s caused us to neglect other things more important. Such as, you ask? As an example of neglect, Friedman complained: “I still can’t get uninterrupted cellphone service between my home in Bethesda and my office in D.C.” Leave it to Tom to undermine his own proposition. But the proposition is clear, and it’s this: “Al Qaeda is about 9/11. We are about 9/12, we are about the Fourth of July—which is why I hope that anyone who runs on the 9/11 platform gets trounced.”

Opposite Friedman’s determination that 9/11 ended on 9/12, is Norman Podhoretz’s belief that 9/11, in his words, “constituted an open declaration of war on the United States, and the war into which it catapulted us was nothing less than another world war.” (He calls it World War IV—the Cold War was World War III.) Podhoretz predicts this world war will last three or four decades, as the Cold War did. If you ask him where we are now, in comparison to the Cold War, he’ll tell you we’re only in 1952 or thereabouts. 9/11, far from making us stupid, finally wised us up—or should have. Podhoretz also knows who he thinks should lead America in wartime: he’s a senior foreign policy adviser to the Giuliani campaign.

Now I suspect the vast majority of Americans don’t think 9/11 is over, but also don’t feel that we’re in a world war. As I said, these are the two opposite poles of the debate. But even if these are two views from the far poles, I think they do frame the debate. This election, to the extent it’s about foreign policy and national security, is about whether Americans believe we’re in a 9/11 war.

That may seem paradoxical, because some people think this election is about the Iraq war. Others think it’s about a possible Iran war. But these are policy subsets of the bigger question framed by Friedman and Podhoretz. How you answer that bigger question will inflect your answer to all the lesser questions.

So Americans first have to decide whether we’re in a war that began on 9/11. Yes, we haven’t had an attack since 9/11. Does that mean 9/11 was a one-off unlucky hit, to which we’ve overreacted with a “war on terror”? Or is the “war on terror”—the fact that we’ve been on the offensive—the real reason 9/11 hasn’t been repeated? (Actually, 9/11 has been repeated—just not here. 9/11 wasn’t followed by 9/12, it was followed by 3/11 in Madrid and 7/7 in London and other attacks.)

Now even Tom Friedman, only one week after his “9/11 is Over” piece, wrote this in another column: “The struggle against radical Islam is the fight of our generation.” He may think the world is flat, but there are some truths even Tom can’t deny. Ironically, his words are almost identical to this snippet from Rudy Giuliani’s website: “Rudy Giuliani believes winning the war on terror is the great responsibility of our generation.” In Giuliani’s view, this makes us “all members of the 9/11 generation.” Maybe you think we are, and maybe you think we aren’t: labeling generations is tricky business. But we’re all certainly post-9/11, in this crucial respect: we’re now aware that we have a determined enemy called “radical Islam” or, as Giuliani called it in his article in Foreign Affairs, “radical Islamic fascism.” If we don’t defeat this enemy, it will strike us again. This means that, like it or not, we’re electing a war president—someone who’ll have to act, every day, not just as our president, but as commander in chief.

Now even the candidates who speak of the “war on terror” against “radical Islam” have different ideas on what the “central front” is. Is it Iraq? Or is it Afghanistan? Maybe it’s always been Iran? Or is it in hearts and minds—the war on ideas? Where should we lay the greater emphasis, where should we deploy the most resources, where should we pull back and where should we push forward, and what should be our mix of hard power and soft power? Who are our true allies, and who are our real adversaries? How important is the spread of democracy to our winning the war?

These are all questions about which reasonable people can differ. But to me, these are subsets of another bigger question. I would put it this way: are we prepared to stand our ground in the Middle East, if that’s what it takes to win?

For decades, the United States didn’t have to stand on the ground in the Middle East. It maintained an off-shore position—it engaged, at times, in what’s been called off-shore balancing. The United States maintained its position through diplomacy, arms sales, economic sanctions—everything short of boots on the ground. The invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq represented a clear break from that past. The United States went on-shore, after some of our enemies were emboldened to cross the oceans and attack us on our shores.

The Iraq war is still enveloped in a fog, but there are people who believe that going on-shore was a mistake, and who want to go back to the off-shore posture. In all the discussion of Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer’s conspiracy theories in their book The Israel Lobby, people overlook the alternative strategy they offer at the end, which is off-shore balancing. Let me quote them:

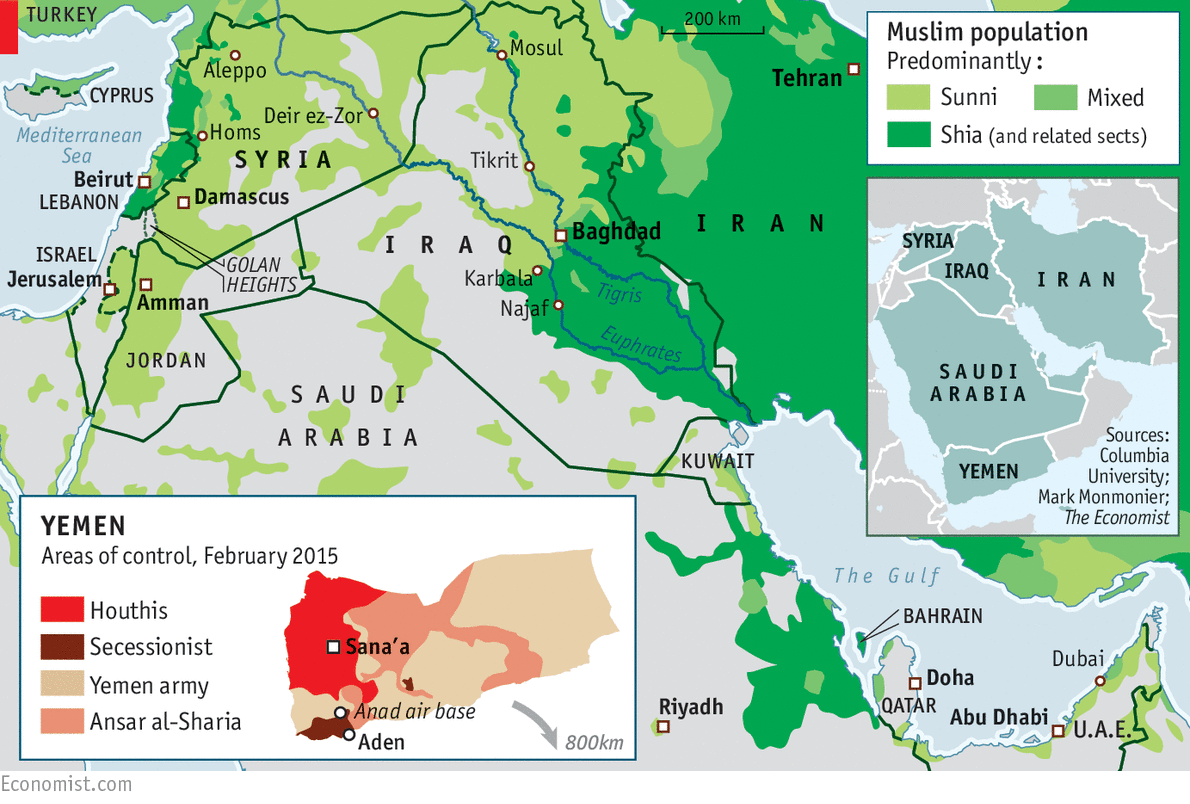

This strategy would be less ambitious in scope but much more effective at protecting US interests in the Middle East…. This strategy categorically rejects using military force to reshape the Middle East, [and] it also recognizes that the United States does not need to control this vitally important region; it merely needs to ensure that no other country does…. Off-shore balancing minimizes the resentment created when American troops are permanently stationed on Arab soil. This resentment often manifests itself in terrorism…. In effect, a strategy of offshore balancing would reverse virtually all of America’s current regional policies…. The United States would withdraw as soon as possible from Iraq… push Israel to give up the Golan Heights [to] drive a wedge between Syria and Iran… [and] cut a deal on Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

Zbigniew Brzezinski has emerged as the champion of this strategy among advisers to candidates. I don’t think it far-fetched to say that a preference for the off-shore posture runs like a thread through the positions of all the Democratic candidates. There are variations, and perhaps Dennis can explain them. Martin Indyk’s piece in the new The American Interest, called “Back to Balancing,” is a more muscular version. But this is the preferred strategy. The crux of the debate among Democrats is who’s willing to promise to get us back off-shore the fastest, and keep us off-shore.

Now the question each of us must answer is this: if we were to go off-shore in the Middle East, who would balance off whom, and who would fill the vacuum? The thread running through the positions of the Republican candidates is that if we move to an off-shore position, if we don’t stand our ground, our allies won’t be able to stand their ground even with our remote support. Our radical Islamist enemies will fill the vacuum. If we don’t strategically control—yes, control—the Persian Gulf region, from the strait of Hormuz up to the Iraqi-Turkish border, our enemies eventually will control it. If we leave Iraq in chaos, our enemies will control it. If Iran acquires a nuclear capability, this corridor will no longer be within our strategic control. Uncertainty will grow, terrorists will be emboldened, oil prices will skyrocket, our enemies will be enriched, and they’ll build and buy weapons of mass destruction. The Pax Americana will be over.

Only American military power, and our perceived willingness to use it, on-shore, can prevent the worst scenarios. Timetables for withdrawals and taking military options off the table constrain us, and just embolden our enemies. This is what Giuliani means when he says we must stay on offense in the war, and that staying on offense will shorten the war. The idea that we can cajole, entice, persuade, and incentivize our allies and even our adversaries into doing our bidding is plain naive. Of course, ultimately it has to be our aim to return to our traditional posture off-shore—but as the victor, not as the vanquished.

I’ve saved the Israeli-Palestinian issue for last, but there are those who would put it first. Why the difference? Because there are different answers to this question: how central is resolving this conflict to U.S. interests in the Middle East?

There was a time not long ago, when people of a certain generation, older than mine, believed as a matter of course that this conflict was the source of all our troubles in the Middle East, and resolving it was the key to fixing the Middle East. Indeed, it was the “Middle East conflict,” solving it was the “Middle East peace process.” Today, serious people no longer take this for granted: Iran’s revolution, three Iraq wars, the rise of Al Qaeda parallel to the Oslo process—today we understand that the Middle East doesn’t have a root conflict. It has many conflicts. Success here doesn’t guarantee success there; the same with failure.

Many of the candidates have records of strong support for Israel. There’s no reason to question them. The more relevant question is who has learned from 9/11 to put the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in proper perspective, and not overvalue the “peace process” as a panacea. Giuliani spoke to this in his Foreign Affairs piece, when he wrote this, and I quote:

The Palestinian people need decent governance first, as a prerequisite for statehood. Too much emphasis has been placed on brokering negotiations between the Israelis and the Palestinians—negotiations that bring up the same issues again and again. It is not in the interest of the United States, at a time when it is being threatened by Islamist terrorists, to assist the creation of another state that will support terrorism. Palestinian statehood will have to be earned through sustained good governance, a clear commitment to fighting terrorism, and a willingness to live in peace with Israel. America’s commitment to Israel’s security is a permanent feature of our foreign policy.

This was misinterpreted in some of the press to mean that Giuliani opposes a Palestinian state. He didn’t say that, but he does dissent from the overvaluation of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. The war against radical Islam takes precedence. A Palestinian state won’t necessarily contribute to winning it, and such a state could ally itself with our enemies, if it doesn’t rest on the firm foundations of good governance and fighting terror.

Significantly, Giuliani affirms that the Palestinians have yet to earn their state. This was once the position of the Bush administration, which seems of late to have abandoned it in a go-for-broke gamble. So we see Secretary of State Rice in Ramallah announcing that “Frankly, it’s time for the establishment of a Palestinian state,” and that such as state is “absolutely essential for the future, not just of Palestinians and Israelis but also for the Middle East and indeed to American interests.” To judge from the situation on the ground, frankly, it may not be the time, nor is it clear in what way its creation is absolutely essential to U.S. interests.

As we’ve seen time and again, such statements only free the Palestinians from doing what needs to be done to earn their statehood. Only by pushing the so-called political horizon back, not forward, is there any chance the Palestinians will run to reach it. The over-privileged “peace process,” as traditionally configured, has had the opposite of its intended effect, making the two-state solution still more remote. It needs to be reengineered.

Well, I got through this opening without mentioning the name of any candidate other than the one I advise. I’ve tried to ask what I think are the key questions on guiding principles. You may prefer different answers to mine, and so may prefer a different candidate. But I hope we can agree that these are the questions. Of course, there are hundreds of lesser policy questions, but these are always changing anyway, and they’ll be different in January 2009 when the next president enters the White House. Ask me about them, and I promise to do my very best to avoid answering them. Thank you.

(For the record: Martin Kramer, a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, is not and has never been an employee of the Institute, which is non-partisan.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.