I summarize four more sessions from my fall course on the introduction to the modern Middle East (Turkey and the Arab lands) at Shalem College in Jerusalem. Below are entries for sessions five through eight. For earlier sessions, go here. As before, I spice up each entry with an insight from the late Bernard Lewis.

Class Five: Islam (reformed) Then Joined Europe. The Tanzimat, the Ottoman reforms of the mid-19th century, are the centerpiece of session five of my intro to the Middle East at Shalem College. Then as now, many in the West complained of misgovernment, corruption, and repression in the East. The Ottoman empire, on the doorstep of Europe, seemed like an affront to enlightened European values. Arbitrary government, a bureaucracy for sale, discrimination against non-Muslim subjects—the list was long. Sound familiar?

Was it that bad? Debatable. But one Ottoman sultan set out both to satisfy Europe and strengthen his own position by pushing through far-reaching reforms. This was Abdülmecid I, the first sultan to speak a European language fluently (French). He reorganized imperial finances, established a civil code and courts outside the Islamic framework, opened a university, formed an education ministry, and more. Abdülmecid announced his plans in two imperial edicts, in 1839 and 1856—promissory notes to European opinion—and he bought the empire time by aligning with the British, who came to his defense, first against an Egyptian invading force, later (in alliance with France) against the Russians in the Crimean War. When it was over, the concert of Europe admitted the Ottomans and recognized the empire’s territorial integrity—until it didn’t.

But the big reform the Europeans demanded was to equalize the status of non-Muslims with that of Muslims in the empire. As Bernard Lewis wrote, in his magisterial Emergence of Modern Turkey, most Muslims viewed this as an “insult and outrage,” and as “a triumph over Islam of the millennial Christian enemy in the West.” The resulting resistance would slow the pace of reforms, but there could be no going back.

It’s hard to interest students in old treaties, but the Treaty of Paris (1856), following the Crimean War, can’t be avoided, since it recognized the Ottoman empire as part of the European system, subject to and guaranteed by its laws (which we now call “international law”).

If you visit the palace at Versailles, you can view this huge painting (three by five meters) that captures the moment. The artist, the Frenchman Édouard-Louis Dubufe, depicts the negotiators of the treaty. The two Ottoman negotiators are here: Mehmed Cemil Bey (the smallish figure by the door in the back), and Ali Pasha (seated on the far right). Contemporary reports say they came well-prepared.

Class Six: Britain’s Veiled Protectorate in Egypt. Exactly one class session: in my course on the modern history of the Middle East, that’s all the time we have to cover Egypt from the British occupation in 1882 to the First World War. Talk about compression. So what’s a must-have for this (sixth) session of the class?

Looming large is Sir Evelyn Baring, later Lord Cromer, who basically ran Egypt as British “agent” and “consul-general” from 1883 to 1907. To this day, he remains enveloped in controversy. He took a dim view of the Egyptian capacity for self-rule: “We have to go back to the doubtful and obscure precedents of Pharaonic times to find an epoch when, possibly, Egypt was ruled by Egyptians. Neither, for the present, do they appear to possess the qualities which would render it desirable… to raise them at a bound to the category of autonomous rulers.” And so he ran the country himself. He stabilized the economy, but couldn’t stop the tide of nationalism.

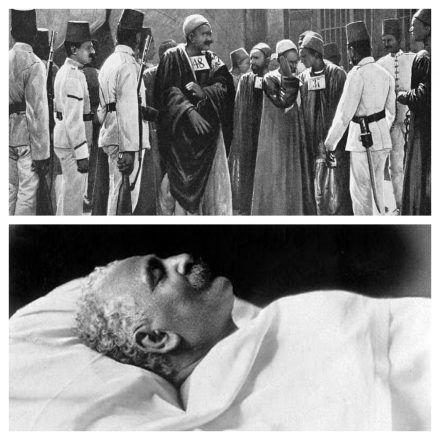

The pigeons came home to roost, so to speak, in 1906, when a party of British officers on a pigeon hunt clashed with villagers in a Nile delta village called Denshawai. An officer died in the altercation, apparently of heatstroke, but several villagers were tried and hanged, others were flogged and sentenced to penal servitude.

The perceived injustice caused a huge uproar. In class, we read the condemnation of Cromer by George Bernard Shaw, and the poem on the executions by Constantine Cavafy. And we read a manifesto by Egyptian nationalist leader Mustafa Kamel, as well as the warden’s report on Ibraham Wardani, the nationalist who in 1910 assassinated Boutros Ghali, by then Egypt’s prime minister, who’d been one of the judges in the Denshawai trial. The stage is set for the later eruption of nationalist revolt against all things British, good or bad.

(My Israeli students also need to hear that in 1903, Theodor Herzl tried to persuade Cromer to open up northern Sinai to Jewish settlement. Cromer feigned interest but eventually nixed the plan. Herzl called him “the most disagreeable Englishman I have ever faced.”)

We end by discussing a passage in Isaiah Berlin’s famous essay, “Two Concepts of Liberty” (1958). True, he writes, Egyptians

need medical help or education before they can understand, or make use of, an increase in their freedom…. First things come first: there are situations in which—to use a saying satirically attributed to the nihilists by Dostoevsky—boots are superior to Pushkin… The Egyptian peasant needs clothes or medicine before, and more than, personal liberty, but the minimum freedom that he needs today, and the greater degree of freedom that he may need tomorrow, is not some species of freedom peculiar to him, but identical with that of professors, artists and millionaires.

But when is “tomorrow” today? It’s a question that much preoccupied Bernard Lewis. But more on that on another occasion.

Images: Above, the accused at the Denshawai trial; below, the assassinated Boutros Ghali in death. (Both, Wikimedia.)

Class Seven: The Last Ottoman Sultan Standing. By the last quarter of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was in salvage mode. It was bankrupt, its armies couldn’t stave off defeat, and its politics stagnated. But the once-glorious empire refused to give up the ghost. This was due, at least in part, to the resolve of its last effective sultan, Abdülhamid II, who reigned for almost 33 years, from 1876 to 1909. Session seven of my intro class on the Mideast at Shalem College revolves around this enigmatic man, who was controversial while he lived, and who remains so.

The last few years have seen something of an Abdülhamid revival in Turkey. He’s been the hero of a hugely popular television drama series, Payitaht Abdülhamid. High production values combine with a sharp disregard for the record of events (plus a dash of antisemitism), to paint Abdülhamid as a devout paragon of Muslim virtue. This perfectly suits the neo-Ottoman agenda of Turkey’s present ruler, who’s more of an Abdülhamid than an Atatürk. (That’s perhaps why it was persistently rumored that the new mega-airport just opened on the edge of Istanbul would be named after Abdülhamid. For now, it’s just Istanbul Airport.)

So who was the real Abdülhamid? You know the trope of the reform-minded prince who comes to power amid great expectations in the West, only to dash them by sliding into the authoritarian mode, or worse. (Sound familiar, Syria- and Saudi-watchers?) Abdülhamid’s first move as sultan was to promulgate a constitution and convene an elected parliament. Perhaps he thought this would prevent the amputation of Christian-populated provinces in the Balkans.

It didn’t, and a year later, Abdülhamid suspended the constitution and disbanded the parliament. It was his own show after that, and as “Turkey-in-Europe” dwindled, he fell back on the Muslim masses of Asia, to whom he promoted himself as savior-caliph. Massacres of Armenians and Assyrians eventually followed, and Abdülhamid became known as the “Red Sultan” in the European press. The later architects of secular Turkey similarly took a dim view of him.

It was Bernard Lewis, in his landmark Emergence of Modern Turkey, who first took a more favorable tack. “Abdülhamid was far from being the blind, uncompromising, complete reactionary of the historical legend,” he wrote (back in 1960). “On the contrary, he was a willing and active modernizer.” Railroads, telegraphs, schools, libraries, museums—he promoted just about any innovation that wouldn’t weaken his grip on power. No doubt, Abdülhamid deserved a rethink, and some historians have done it meticulously and fairly. But the present fad for him is over the top.

As I remind my Israeli students, Herzl met Abdülhamid in a futile attempt to extract some kind of charter for Zionism. It’s the stuff for another course, but we read Herzl’s verdict from his diary: “My impression of the Sultan was that he is a weak, cowardly, but thoroughly good-natured man. I regard him as neither crafty nor cruel, but as a profoundly unhappy prisoner in whose name a rapacious, infamous, seedy camarilla perpetrates the vilest abominations. If I didn’t have the Zionist movement to look after, I would now go and write an article that would give the poor prisoner his freedom.” It’s ironic, given the Elder-of-Zion treatment of Herzl in the current Turkish telenovela on Abdülhamid.

The Ottoman Empire outlasted Abdülhamid (he was thrown out in a revolution in 1909), but not by long. That it lasted as long as it did, may well have been to his credit.

(Image: Abdülhamid on his way to, or back from, Friday prayer. Herzl gives a vivid account of this spectacle in his diary. “Within less than an hour the most magnificent images rushed past us…”)

Class Eight: The War that Made the Middle East. It’s no small challenge to pack the entire First World War into one session (the eighth) of my intro to the Mideast at Shalem College. So I always fail, and end up running over into the next session. In large measure, the Middle East today is the product of that war, so it’s not remote history at all.

There’s the pre-war calculation that put the Ottomans into the war on the side of Germany. There’s the war itself, on multiple fronts, from Gallipoli to Mesopotamia, from Allenby in Palestine to the Arab Revolt (advised by Peter O’Toole… oops, Lawrence of Arabia). There’s the Ottoman-Russian struggle and the internal war on the Armenians.

In parallel, there’s the (double?) dealing: the British promises (such as they were) to the Arabs, the Sykes-Picot partition accord, the Balfour Declaration. Lots of maps to decipher, lots of texts to parse, and it can overwhelm the undergrad student. On top of that, part of the session gets eaten up explaining what the wider war was all about. That involves explaining why 20 million died, just as an aside.

In the end, I try to impress upon the students one major takeaway: the war tore up the old map, and the new one, based on a mix of great power interests and “national self-determination,” produced an endemic instability. But as I also remind my Israeli students, for the foresighted (such as the Zionists), the war provided a one-and-only opportunity to realize fantastic plans. The upset was total; no one in 1914 could have imagined what the Middle East would look like only 20 years later.

One aspect of the war was a source of grief for Bernard Lewis. He took the view that the Ottoman regime didn’t have a plan to destroy the Armenians, whose wholesale expulsion and massacre in 1915 didn’t constitute genocide. He said as much in an interview to France’s leading newspaper in 1993, and Armenian groups took him to court over it. It’s a complicated story; you’ll find Lewis’s side of it in chapter 11 (“Judgment in Paris”) of his memoirs.

His own final verdict is interesting: “If the word ‘genocide’ is to be used in its original and legal meaning… then the appropriateness of this term to the Armenian massacres of 1915 remains unproven. However, language changes, and looking at this again twenty years later it is clear that the word ‘genocide’ has developed a broader and less precise meaning today.” I suppose that meant Lewis came to acquiesce in the historicity of the Armenian genocide, in line with current-day usage. The question is, at what point does the term “genocide” become so elastic and ubiquitous in common usage that it ceases to move us? We may be past that point already.

Image: General Allenby, fresh from his conquest of Jerusalem, reads his proclamation to the city’s inhabitants, December 11, 1917 (Wikimedia).

You must be logged in to post a comment.