Henry Siegman, who must spend every waking hour hating Israel, has a piece in the London Review of Books, which is never complete without an Israel-bashing tirade. This one is called simply “Israel’s Lies.” Siegman spends a lot of time faulting Israel for the breakdown of the previous six-month cease-fire with Hamas, reached through Egyptian mediation in June 2008. In one passage, he accurately reports the quid pro quo of the cease-fire:

[The cease-fire] required both parties to refrain from violent action against the other. Hamas had to cease its rocket assaults and prevent the firing of rockets by other groups such as Islamic Jihad… and Israel had to put a stop to its targeted assassinations and military incursions.

Correct. But only a couple of paragraphs earlier, he set up the cease-fire as an entirely differently deal—and accused Israel of violating it:

Israel, not Hamas, violated the truce: Hamas undertook to stop firing rockets into Israel; in return, Israel was to ease its throttlehold on Gaza. In fact, during the truce, it tightened it further.

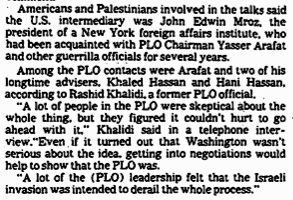

Therefore according to Siegman, Israel violated the cease-fire before Hamas fired a single rocket, by reneging on its supposed commitment to ease sanctions. Rashid Khalidi, writing in the New York Times, went even further: “Lifting the blockade,” he wrote, “along with a cessation of rocket fire, was one of the key terms of the June cease-fire between Israel and Hamas.” (My emphasis.)

None of this is true.

First of all, contra Khalidi, Israel did not agree to “lifting” of the “blockade,” only to easing it. At the time, the Economist reported the cease-fire thus (my emphasis):

The two sides agreed to start with three days of calm. If that holds, Israel will allow some construction materials and merchandise into Gaza, slightly easing an economic blockade that it has imposed since Hamas wrested control of the strip.

And Israel did just that: it slightly eased the sanctions on some construction materials and merchandise. Siegman falsely claims that Israel “tightened” its “throttlehold” on Gaza after the cease-fire, and that this is confirmed by “every neutral international observer and NGO.” Untrue. The numbers refuting him appear in the last PalTrade (Palestine Trade Center) report on the Gaza terminals, published on November 19, as part of its “Cargo Movement and Access Monitoring and Reporting Project.” The report says the following (my emphasis):

Following the announcement of the truce ‘hudna’ on June 19, 2008 and took effect on June 22, a slight improvement occurred in terms of terminals operation times, types of goods, and truckloads volume that [Israel] allowed to enter Gaza Strip.

This is exactly what Israel had agreed to permit. Here is the table from the PalTrade report, comparing average monthly imports before the Hamas coup (June 12, 2007), between the coup and the “truce,” and then after (i.e., during) the “truce” (through October 31). (If you can’t see the table below, click here).

As is obvious from this table, Israel did ease sanctions during the cease-fire. The average number of truckloads per month entering Gaza during the cease-fire rose by 50 percent over the period before the cease-fire, and Israel also allowed the import of some aggregates and cement, formerly prohibited. (No metal allowed, of course—it’s used to make rockets.) Israel did not allow more fuel, but the PalTrade report notes that fuel brought from Egypt through the tunnels “somewhat made up the deficit of fuel that entered through Nahal Oz entry point.” (For Israel’s own day-by-day, crossing-by-crossing account of what went into Gaza during the cease-fire, go here. This account also puts the increase of merchandise entering Gaza at 50 percent.)

Why do the Khalidi and Siegman errors (or lies, if made knowingly) matter now? If you believe Khalidi’s claim that the last cease-fire included “lifting the blockade,” you might say: why shouldn’t Israel agree to lift it in this one? Or if you believe Siegman’s claim that Israel tightened the sanctions at the crossings during the cease-fire, you might say: Israel shortchanged the Palestinians once, so the next deal on the crossings has to have international guarantees. But in both cases, you’d be relying on entirely bogus claims.

Israel has a compelling strategic reason to keep the sanctions in place. (I say sanctions and not blockade, because Israel doesn’t control the Egyptian-Gazan border, and so cannot impose a true blockade.) Israel’s sanctions are meant to squeeze the “resistance” out of the Hamas regime—and, if possible, to break its monopoly on power in Gaza. Unless these goals are met, at least in part, it’s lights-out for any peace process. And as long as sanctions don’t create extreme humanitarian crises—as opposed to hardships—they’re a perfectly legitimate tool. It was sanctions that ended apartheid in South Africa, kept Saddam from reconstituting his WMD programs, got Qadhafi to give up his WMD, and might (hope against hope) stop Iran’s nuclear program.

Hamas owes everything not to its feeble “resistance,” but to the tendency of the weak of will or mind to throw it lifelines. It’s now demanding that the sanctions be lifted, and the usual chorus is echoing the cynical claims of a tyrannical and terrorist regime that shows no mercy toward its opponents, Israeli or Palestinian. Supporters of peace shouldn’t acquiesce in another bailout of its worst enemy. It’s time to break the cycle, and make it clear beyond doubt that the Hamas bubble has burst. The way to do that is to keep the sanctions in place.

A reader sends me yet another piece of contemporary evidence from the mainstream U.S. media for Rashid Khalidi’s PLO connection, to add to the

A reader sends me yet another piece of contemporary evidence from the mainstream U.S. media for Rashid Khalidi’s PLO connection, to add to the

You must be logged in to post a comment.